Check list

Good LLM quiz questions 🤖

By Urvi 🎉

Question: Can a network with clustering coefficient = 1 be small-world?

Expected Answer: Student’s Answer: No, that’s just a complete graph (shortest path length = 1, but trivial).

LLM’s Answer: LLM’s Answer: Yes, a network with a clustering coefficient of 1 can be a small-world network. The Watts-Strogatz model demonstrates this precisely. A clustering coefficient of 1 indicates that every node is part of a fully connected “clique” with its immediate neighbors …

By Sarah 🎉

Question: What can we conclude about the small world-ness of a network where it’s average clustering coefficient and global clustering coefficient are both equal to 1?

Expected Answer: We conclude it is not a small world network since having both coefficients equal to 1 signifies a fully connected network which therefore cannot also be small-world.

LLM’s Answer: The small-world property of a network, characterized by both high clustering and short average path lengths, is concluded when both the average clustering coefficient and the global clustering coefficient are equal to 1. This signifies that every node in the network is highly connected to its immediate neighbors, forming dense local communities (high clustering). Simultaneously, it indicates that, on average, any two nodes in the network are only a few steps away from each other (short average path length).

By Amahury 🎉

Question: True or False (justify briefly): The simple cycle graph C_N with N ≥ 5 is small-world (σ > 1) under the Humphries–Gurney definition when using C as transitivity and an Erdős–Rényi baseline with the same N and M.

Expected Answer: Student’s Answer: False. C_N has no triangles, so C = 0. With an ER baseline (same N, M) we have C_rand > 0 and L/L_rand is finite, hence σ = (0/C_rand)/(L/L_rand) = 0 < 1.

LLM’s Answer: The statement “The simple cycle graph C_N with N ≥ 5 is small-world (σ > 1) under the Humphries–Gurney definition when using C as transitivity and an Erdős–Rényi baseline with the same N and M” is true.

Module 5: Clustering 🧩

What we will learn in this module:

- What is community structure in networks? 🌐

- How to operationalize community structure? 🔬

- How to find communities in networks? 🔍

- Limitations of community detection 🚧

Keywords: community detection, assortativity, modularity, resolution limit, rugged landscape, random graph, label switching algorithm, Louvain algorithm, stochastic block model, the configuration model.

What is Community? 🐦

- “Birds of a feather flock together”

- In networks, communities are groups of nodes with similar connection patterns.

- They can reflect:

- Homophily: similar nodes connect.

- Functional groups: nodes collaborating for a purpose.

- Hierarchical structure: communities within communities.

How to Find Communities?

- Pattern matching approach

- Define a community pattern and find it.

- Optimization approach

- Maximize a quality function of a partition.

- Generative model

- Fit a generative model to the network.

Pattern Matching

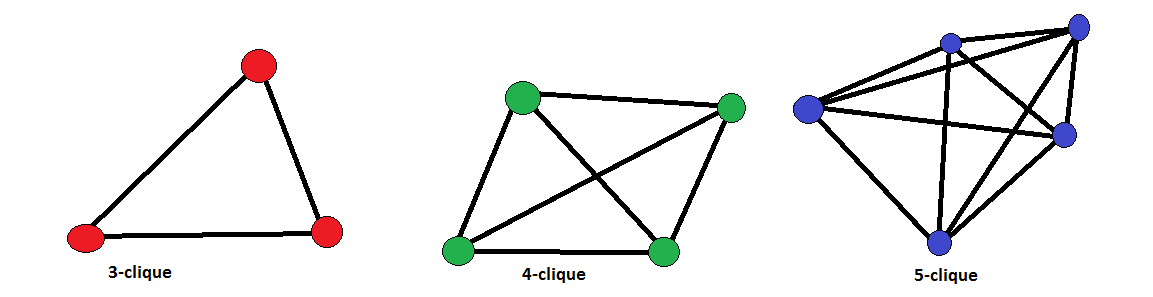

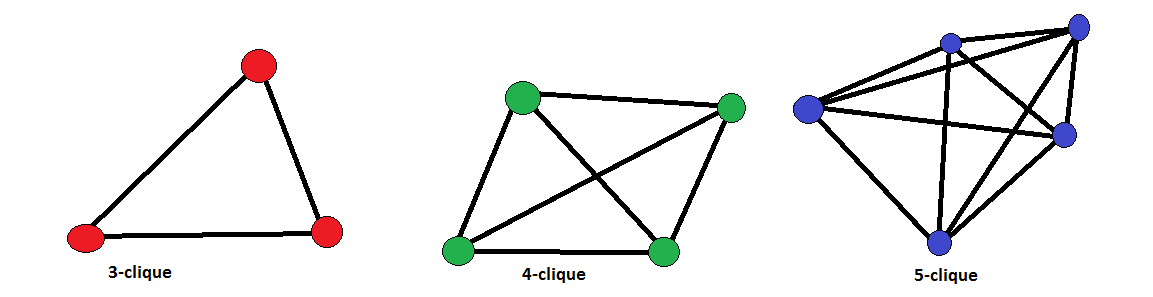

Pattern Matching 🧩: Cliques

- Clique: a group of nodes where everyone is connected to everyone else.

- The strictest definition of a community.

- Often too rigid for real-world networks.

Image of cliques

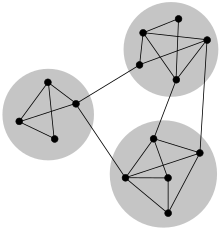

Clique Percolation (Palla 2005 Nature)

- Idea: Communities are formed by overlapping cliques

- Start with all k-cliques in the network

- Two k-cliques are connected if they share k-1 nodes

- Communities are connected components in this “clique graph”

Advantages:

Allows overlapping communities, based on strong local cohesion, and parameter \(k\) controls the number of communities.

Issue of cliques

Real-world groups are rarely perfect cliques. We relax the definition along three dimensions:

- Degree: Not every node needs to be fully connected.

- Density: The group doesn’t need all possible edges.

- Distance: Members can be a few steps away from each other.

Pen and Paper Exercises ✍️

Degree Relaxation: k-plex and k-core

- k-plex: each node can miss connections to at most \(k\) others in the group.

- k-core: each node has at least \(k\) connections within the group.

Density Relaxation: \(\rho\)-dense subgraph

- A \(\rho\)-dense subgraph has at least a fraction \(\rho\) of all possible internal edges.

- Useful for communities that are highly, but not perfectly, interconnected.

Distance Relaxation: n-clique, n-clan, n-club

- n-clique: every pair of nodes is within \(n\) steps of each other.

- n-clan: every pair of nodes is within \(n\) steps of each other within the group.

- Captures communities knit by short, internal paths, not just direct ties.

Hybrid Approaches

Combine dimensions to capture tightly-knit community structures.

- k-truss: every edge must be part of at least \(k-2\) triangles. Emphasizes triadic closure.

- \(\rho\)-dense core: balances high internal density with sparse external connections.

Optimization Approach 🔍

Overview: Optimization Approach

- Define a quality function for a partition of nodes into communities.

- Search for the partition that maximizes (or minimizes) this function.

- Examples:

- Graph Cut

- Balanced Cut

- Modularity

Graph Cut 🔪

Goal: Minimize the number of edges needed to cut to separate the graph into communities. \[ \text{argmin}_{V_1, V_2} \text{Cut}(V_1, V_2) = \sum_{i \in V_1} \sum_{j \in V_2} A_{ij}, \]

where \(V_1\) and \(V_2\) are the disjoint sets of nodes (i.e., \(V_1 \cap V_2 = \emptyset\) and \(V_1 \cup V_2 = V\)), and \(A_{ij}\) is the adjacency matrix.

This problem statement is incomplete 🫣. Find out what’s missing by playing with the following game. Graph Cut Problem 🎮

Balanced Cut ⚖️

To avoid trivial cuts, we need to balance community sizes.

Ratio Cut: Penalizes small communities by normalizing by size. \[ \text{RatioCut}(\{V_c\}) = \sum_c \frac{\text{Cut}(V_c, V \setminus V_c)}{|V_c|} \]

Normalized Cut: Normalizes by community volume (sum of degrees, i.e., \(\text{vol}(V_c) = \sum_{i \in V_c} k_i\)). \[ \text{N-Cut}(\{V_c\}) = \sum_c \frac{\text{Cut}(V_c, V \setminus V_c)}{\text{vol}(V_c)} \]

We will learn how to solve these problems in Module 08!

So is the problem solved?

- Suppose that we could get a good partition in terms of the objective function.

- But any method has some limitations. What do you think they are 🤔? How would you address that?

- # of communities need to be specified

- Favor balanced communities

Ratio Cut: \[ \text{RatioCut}(\{V_c\}) = \sum_c \frac{\text{Cut}(V_c, V \setminus V_c)}{|V_c|} \]

Normalized Cut. \[ \text{N-Cut}(\{V_c\}) = \sum_c \frac{\text{Cut}(V_c, V \setminus V_c)}{\text{vol}(V_c)} \]

Modularity

Modularity is perhaps the most celebrated, yet most controversial, approach to community detection.

Modularity is:

- able to determine the # of communities in a network

- easily optimized

- an optimal method for planted partition model

Key idea: Modularity finds communities that are not just densely connected, but denser than random chance.

The Ball and String Game 🎨🧵

Imagine colored balls (nodes) and strings (edges).

- Count how many strings connect balls of the same color.

- Cut all strings, throw the ends in a bag, and draw them randomly.

- Modularity = (1) - (2)

Modularity Formula

\[ Q = \frac{1}{2m} \sum_{i,j} \left[ A_{ij} - P_{ij} \right] \delta(c_i, c_j) \]

- \(A_{ij}\): Adjacency matrix (1 if edge exists, 0 otherwise).

- \(P_{ij}\): Probability of an edge between nodes \(i\) and \(j\) in the null model. For the configuration model, \(P_{ij} = \frac{k_i k_j}{2m}\).

- \(\delta(c_i, c_j)\): 1 if nodes \(i\) and \(j\) are in the same community, 0 otherwise.

- \(m\): Total number of edges.

- \(k_i\): Degree of node \(i\).

Modularity Maximization in Action

Let’s play with it!

Limitations of Modularity

Modularity is powerful, but not perfect.

Resolution Limit: Fails to detect communities smaller than a certain scale, which depends on the size of the whole network. It might merge small, distinct communities.

Spurious Communities: Can “find” communities even in random networks where none exist. A high modularity score is not a guarantee of meaningful communities.

Degeneracy: Many different partitions can have similarly high modularity scores.

Modularity on Random Graphs

- A high modularity score doesn’t always mean we’ve found meaningful communities.

- Sparse networks tend to have higher modularity scores.

- We can’t compare modularity scores across different networks!

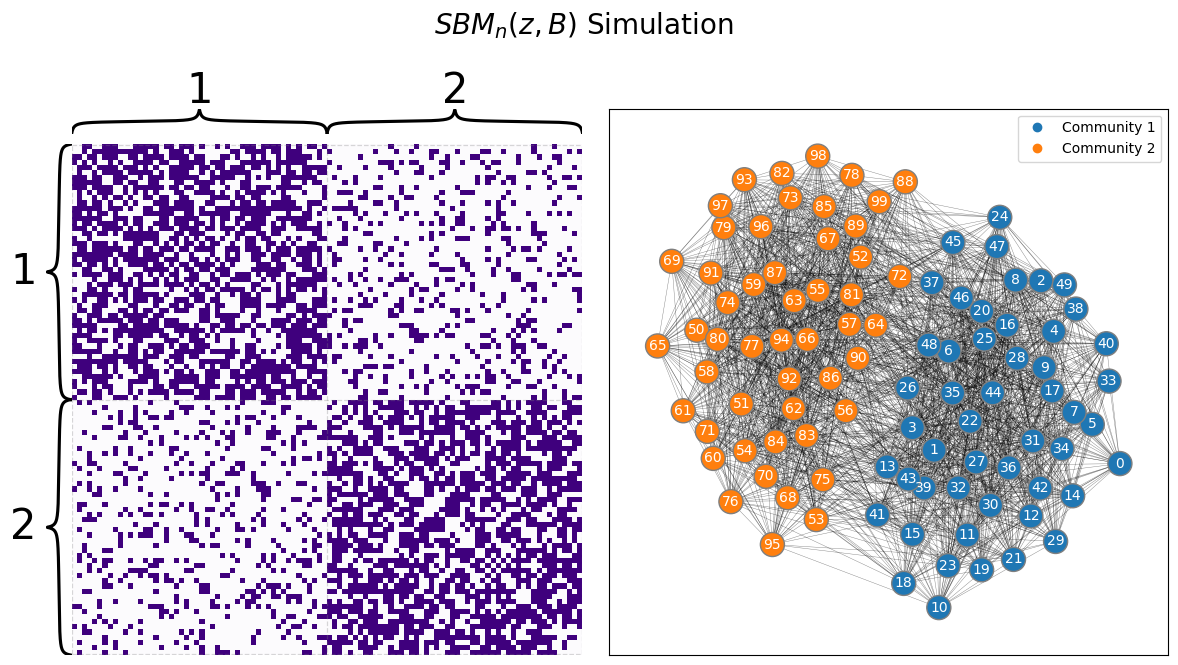

Probabilistic Approach: Stochastic Block Model (SBM) 🎲

Stochastic Block Model (SBM)

Instead of defining what a community is, SBM defines how a network is generated from communities.

- It’s a generative model for networks with community structure.

- Nodes are assigned to blocks (communities).

- SBM specifies the probability \(p_{c_i, c_j}\) of an edge between two nodes in blocks \(c_i\) and \(c_j\) as:

\[ P(A_{ij} = 1 | c_i, c_j) = p_{c_i, c_j} \]

The SBM extends the notion of communities, i.e., a community is a group of nodes that connect to othe nodes in a similar way.

Allow for more broad definitions of communities.

- Assortative communities: Densely connected within and sparsely connected between.

- Disassortative communities: Sparsely connected within and densely connected between.

- Mixed communities: Core-periphery structure.

Given a network, we can infer the most plausible community structure that generated it (if it was generated by SBM) by maximizing the likelihood function, i.e.,

\[ \begin{aligned} &\text{argmax}_{c_1, \ldots, c_n, \theta} \sum_{i<j} \ell_{ij}(c_i, c_j, \theta), \\ &\ell_{ij} = A_{ij} \log p_{c_i, c_j} + (1 - A_{ij}) \log (1 - p_{c_i, c_j}), \end{aligned} \]

where \(c_i\) is the community of node \(i\), \(\theta\) is the parameters of the SBM, and \(p_{c_i, c_j}\) is the probability of an edge between two nodes in blocks \(c_i\) and \(c_j\).

SBM is a generative model for networks with community structure.

It can generate networks with community structure.

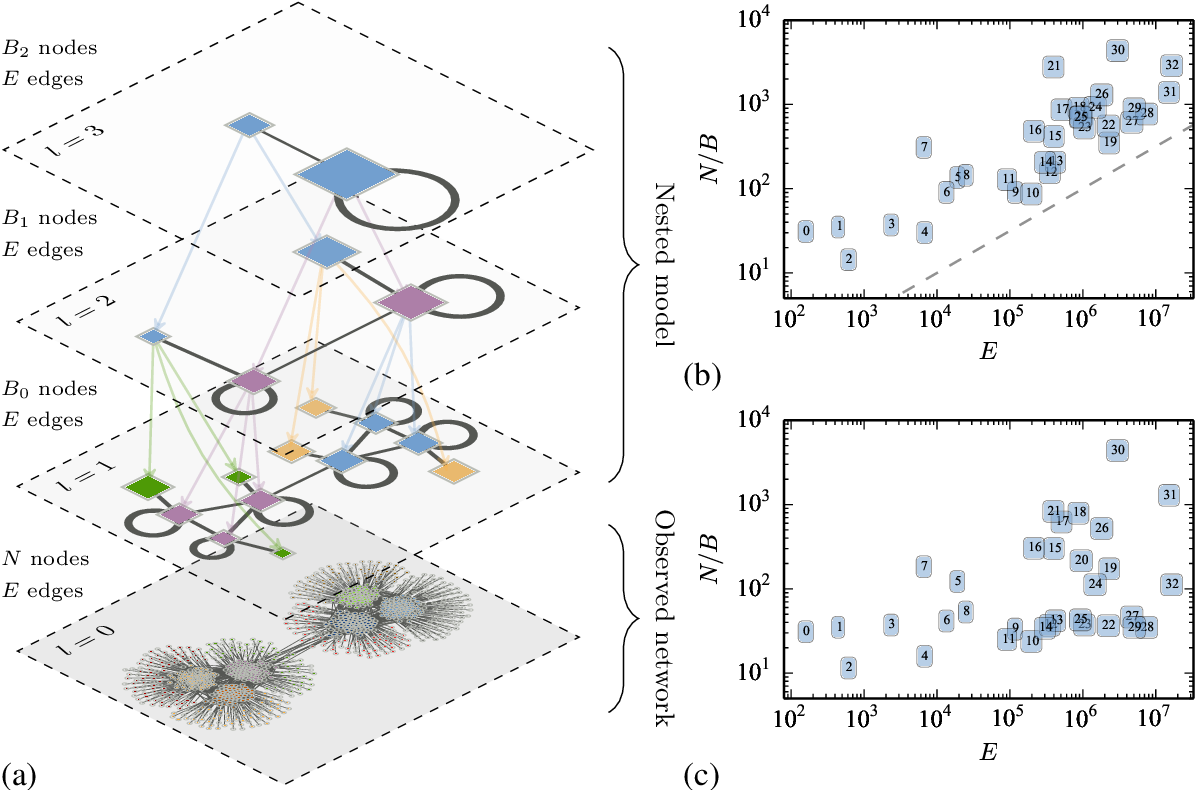

Extensions of SBM

SBM often produces homogeneous degree distributions when the number of communities is small, making it unsuitable for networks with heterogeneous degree distributions.

dcSBM addresses this limitation, and often yields more meaningful communities than the standard SBM.

Hierarchical SBM (hSBM): Models communities within communities, capturing nested structures. This SBM is free from the resolution limit problem!

SBM Inference Methods

There are several ways to fit an SBM:

- Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE): Fast, but can be prone to getting stuck in local optima.

- Bayesian Inference: More robust, can handle model selection (finding the number of blocks), but computationally expensive.

- Spectral Methods: Very fast, used for initialization.

- Belief Propagation: Fast and accurate on sparse, tree-like graphs.

Which one should we use?

It depends on your network and your question!

- For a quick look, Louvain/Leiden (modularity-based) are fast and popular.

- For a more principled approach that can avoid some of modularity’s pitfalls, SBM is a great choice.

- There is no “best” algorithm for all cases (“No Free Lunch” theorem).

- Always be critical of the communities you find!

Further Reading

- Fortunato, S. (2010). Community detection in graphs. Physics reports, 486(3-5), 75-174.

- Peel, L., Larremore, D. B., & Clauset, A. (2017). The ground truth about metadata and community detection in networks. Science advances, 3(5), e1602548.

- Newman, M. E. (2016). Equivalence between modularity optimization and maximum likelihood methods for community detection. Physical Review E, 94(5), 052315.

- Hric, D., Peixoto, T. P., & Fortunato, S. (2016). Network structure, metadata, and the prediction of missing nodes and annotations. Physical Review X, 6(3), 031038.