Networks

1 Networks are everywhere and they matter

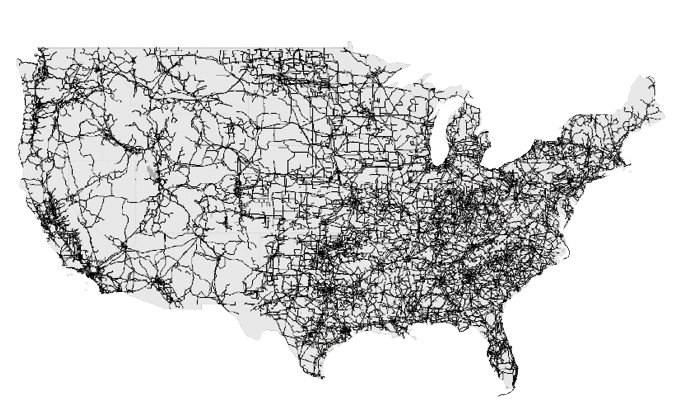

In 2009, the H1N1 influenza pandemic started in Mexico and spread around the world. Dirk Brockmann and Dirk Helbing tracked how the disease reached different countries and made a surprising discovery that would revolutionize how we understand spreading processes.

The most natural way to think about disease spread is through geographic distance. If you looked at a traditional world map, you might expect the disease to spread in expanding circles - first to nearby countries like Guatemala and the United States, then gradually to more distant places. But look at what the data actually shows:

Distance does explain the arrival time to some extent - there’s a rough trend where farther places tend to be infected later (C, D, E). But it doesn’t tell the whole story. At the same distances, some cities experienced early arrival while others experienced much later arrival. What explains this variation?

This mystery was solved by Dirk Brockmann and his colleagues, who realized that disease spread follows the hidden geometry of mobility networks - not geographic maps. Air travel connections, not physical distance, determined how quickly the pandemic reached different parts of the world.

See (Brockmann and Helbing 2013) for more details.

The H1N1 example above reveals a fundamental truth: network structure determines how things spread. Geographic distance became irrelevant once we understood the underlying mobility network. This principle extends far beyond disease outbreaks.

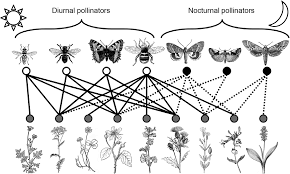

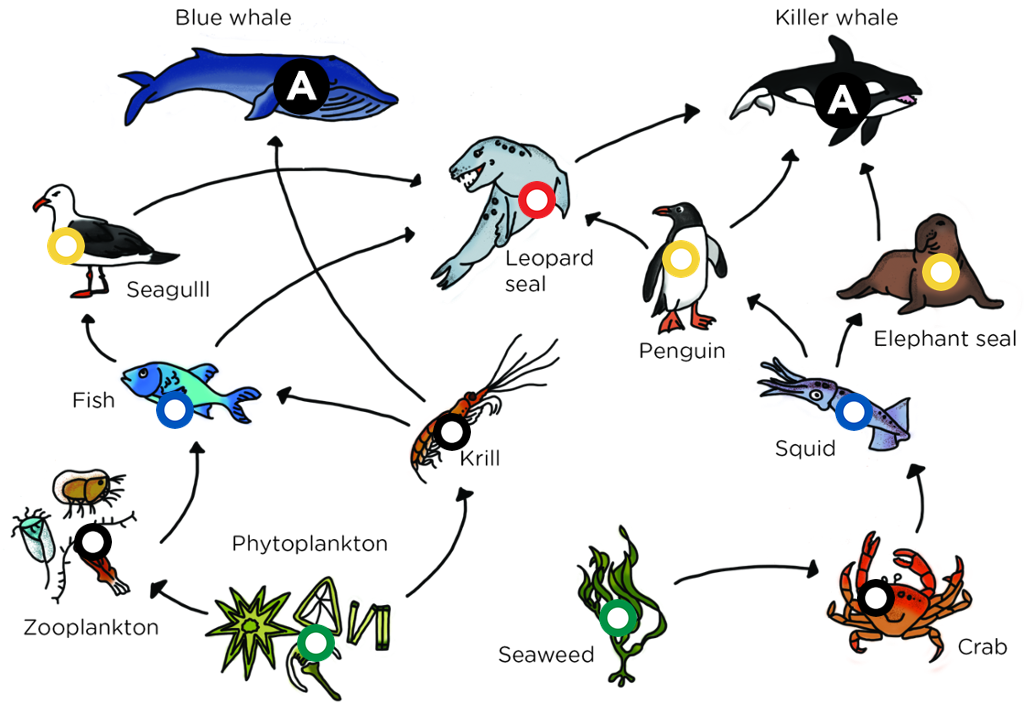

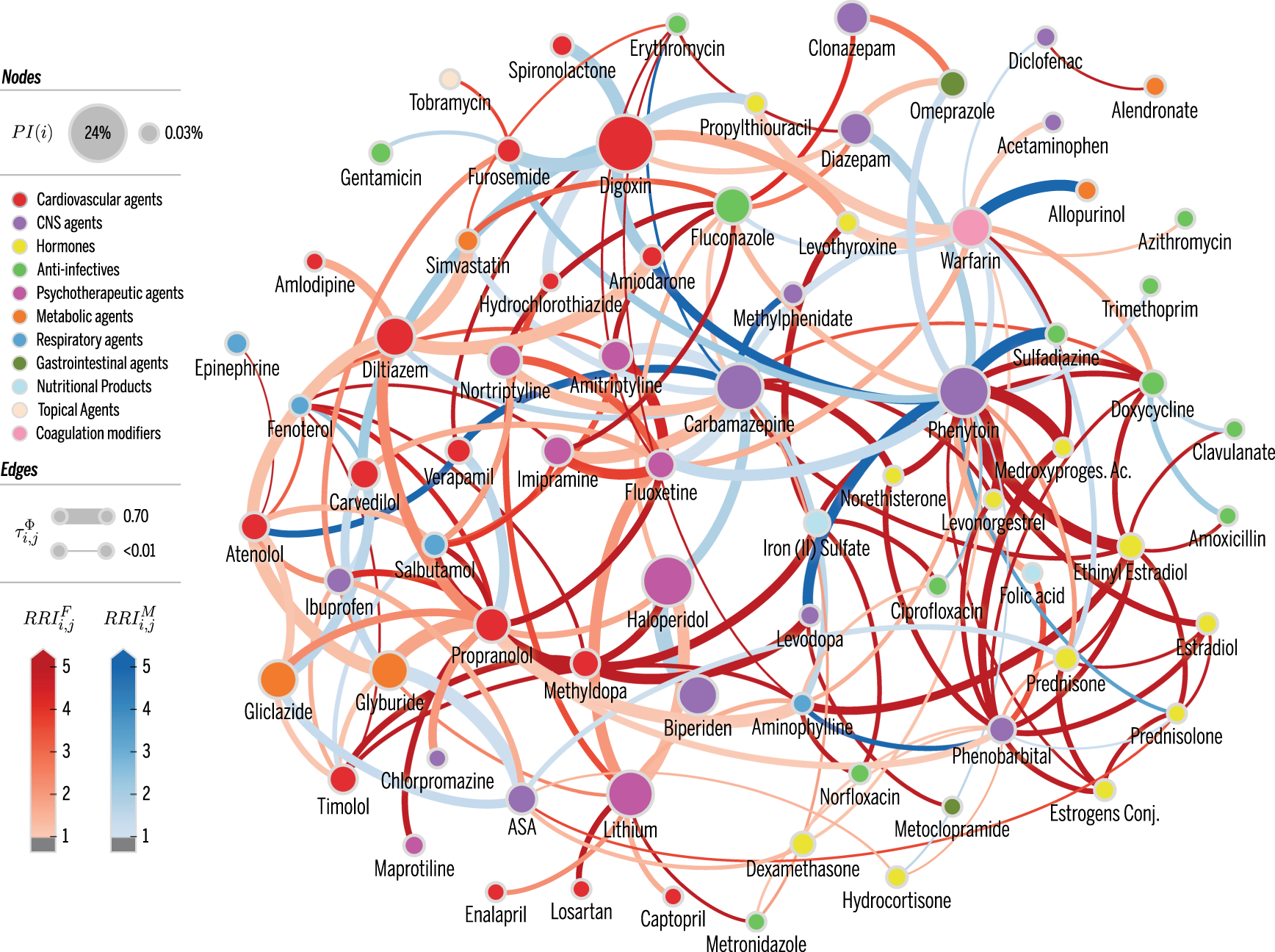

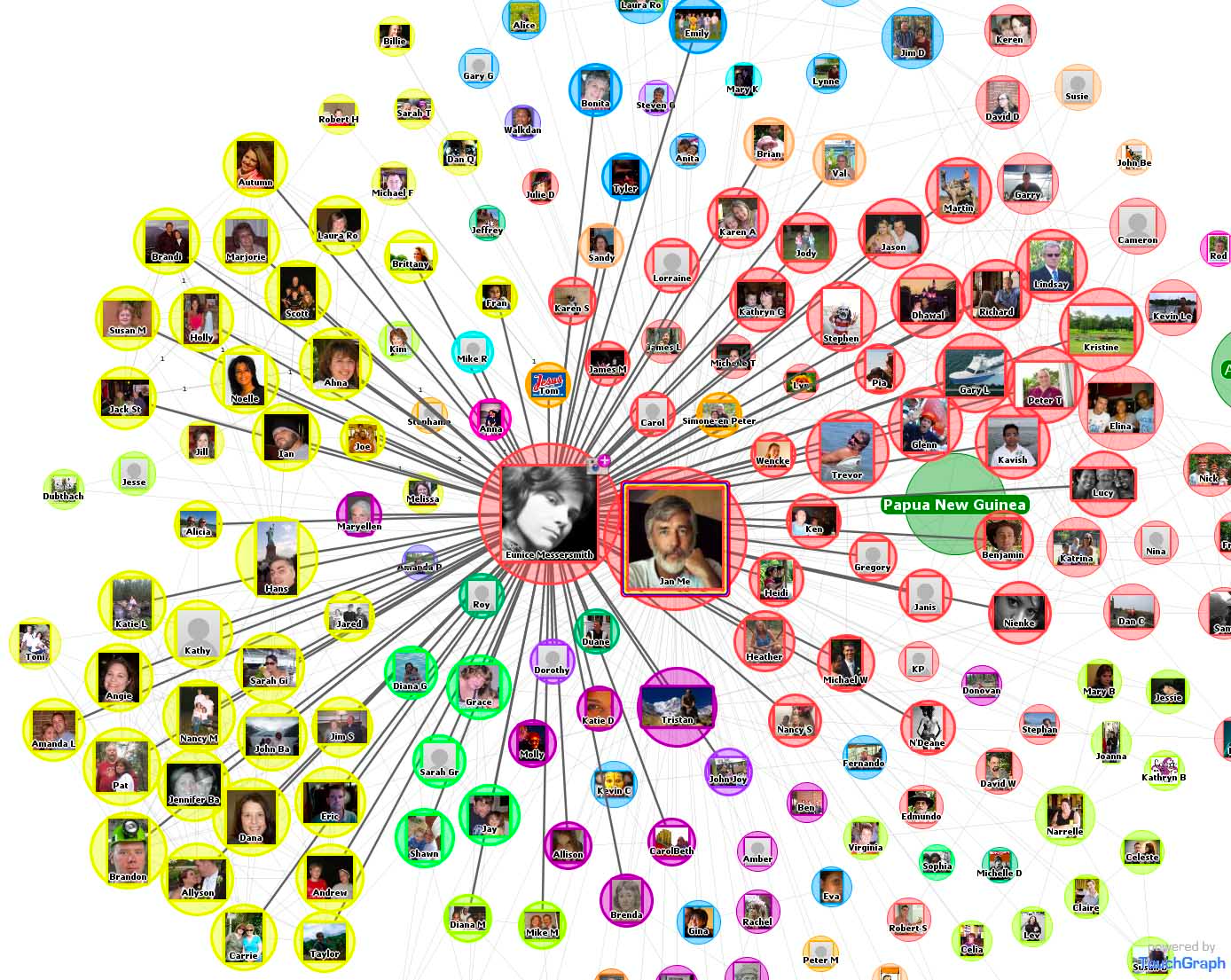

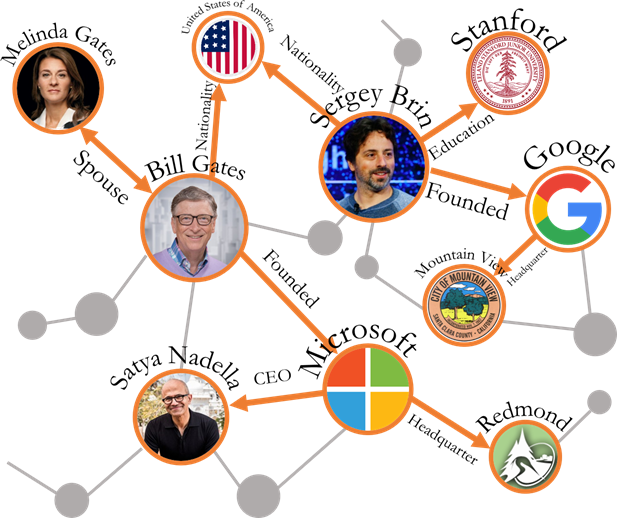

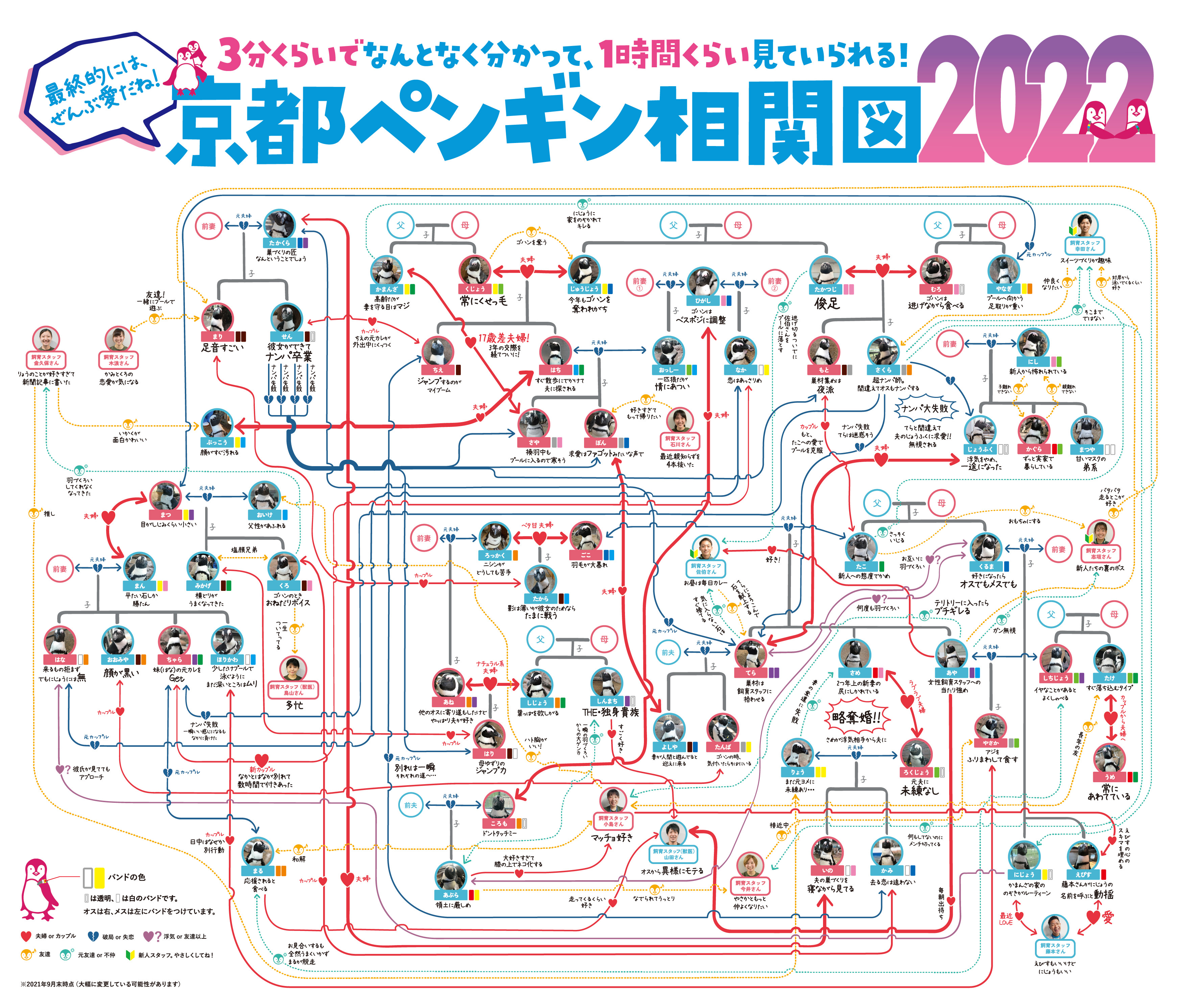

Networks are everywhere. Look around you: plants depend on pollinators in ecological networks, predators and prey form intricate food webs, your brain operates through neural networks, and modern medicine maps drug interactions. At the molecular level, proteins interact in complex networks that sustain life. Socially, we’re connected through friendship networks, while globally, financial institutions form interconnected webs that can trigger worldwide crises. Every flight you take follows airport networks, every light switch connects to power grids, and every river flows through branching networks to the sea. Even the internet connecting you to this text and the knowledge graphs organizing human understanding - all are networks.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/8747607969_65098e4af6_o-f3ebcfa0d1894613995f1c086d1442ac.png)

2 How to represent a network

Although networks come from vastly different fields, we can represent them all using the same universal language 😉. Whether we’re studying brain connections, protein interactions, or social relationships, the mathematical representation remains identical. This abstraction is what makes network science so interdisciplinary.

A network is simply a collection of nodes connected by edges. Despite this simplicity, it’s one of the most powerful abstractions we have for understanding complex systems.

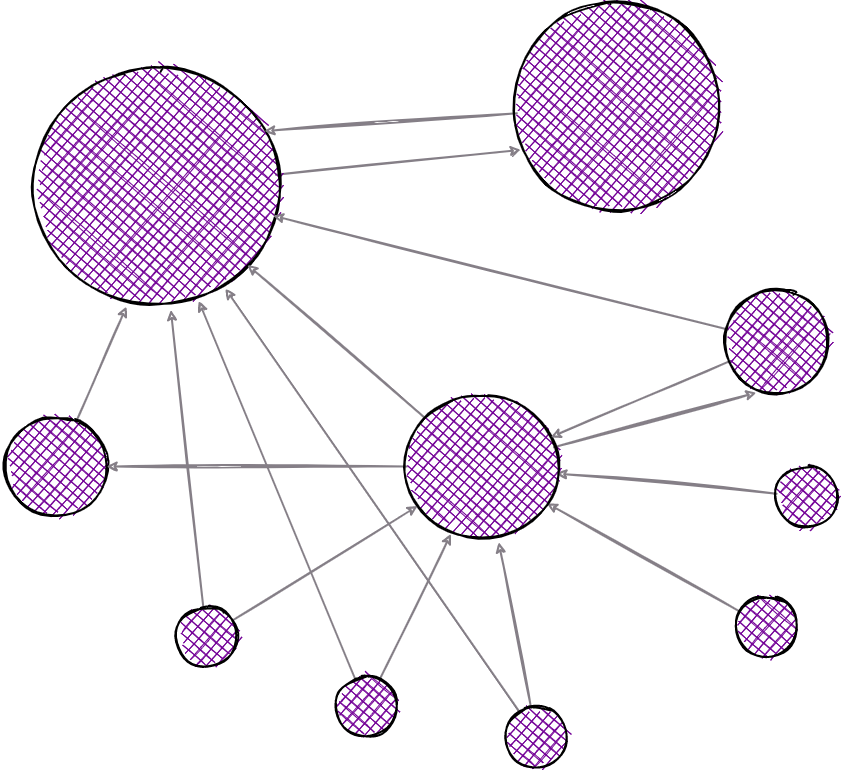

We can represent any network in two equivalent ways. Schematically, we draw them as dots and lines - nodes connected by edges, as shown in this network diagram:

While the schematic representation is useful, things can get complicated as soon as the network becomes large. Also, we want to represent data quantitatively to obtain a quantitative understanding of network properties and behaviors.

Tables are a natural way to represent networks. The idea is to list the pairs of nodes that are connected by an edge. For example:

| Source | Target |

|---|---|

| Node1 | Node2 |

| Node1 | Node3 |

| Node2 | Node3 |

| Node2 | Node4 |

| Node3 | Node5 |

This is called an edge table. Each row represents a connection between two nodes. Once we write down networks in this tabular format, we can apply the same analytical tools regardless of the domain - whether it’s routers, people, neurons, or molecules.

3 Are we done with networks?

If we can represent a network in a table—a familiar data format that can be analyzed by statistical methods, machine learning, and other tools—can we just use these tools to analyze networks? Why do we need to learn network science?

Long story short, a network is not just a collection of nodes and edges. They work in tandem to create a complex system. And this view—that a system is not just a collection of parts—represents a critical shift in science.

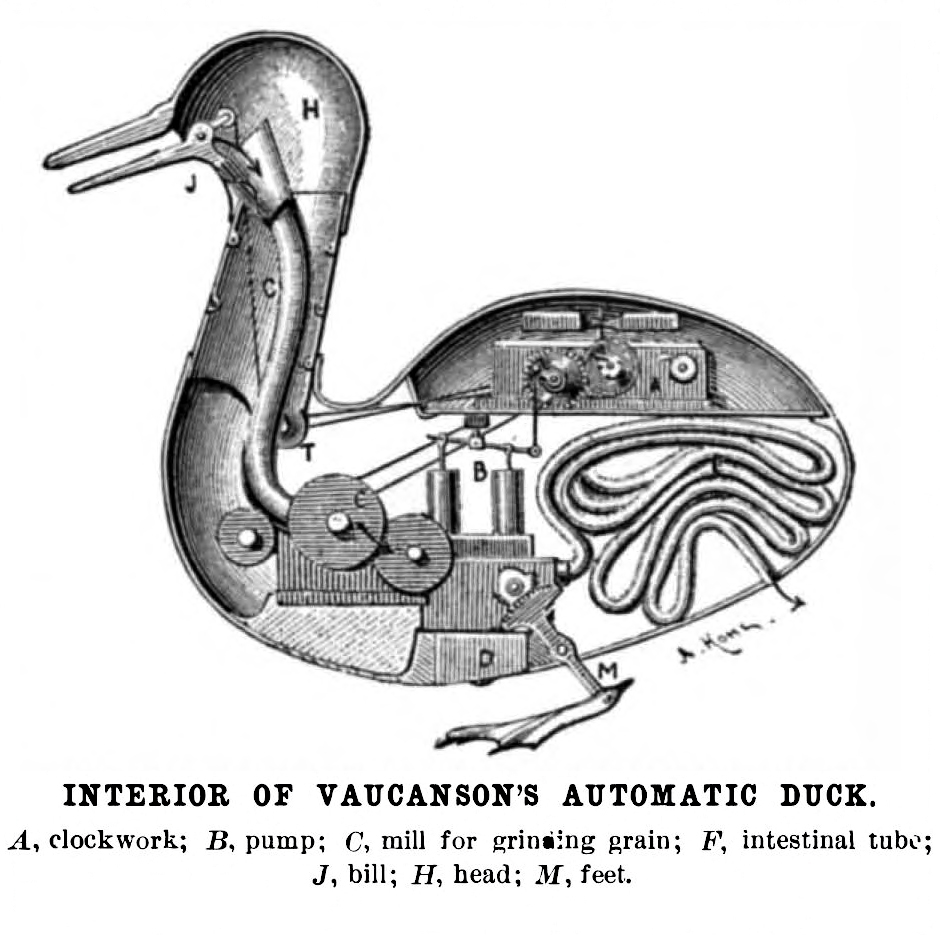

For centuries, scientists believed in reductionism. If you could create modules that function like duck organs and assemble them together, the machine would eventually behave like a duck. Vaucanson’s 18th century Digesting Duck seemed to prove this approach worked remarkably well: break down complex systems into fundamental components, understand each part, then reassemble them to understand the whole.

Find more details in Wikipedia

However, scientists began to realize that not all systems can be decomposed into units that provide sufficient understanding of the system as a whole. Networks represent a fundamental challenge to reductionist thinking because their most important properties emerge from the interactions between components, not from the components themselves. You can understand every individual neuron in the brain, but this won’t tell you how consciousness emerges. You can analyze every person in a social movement, but this won’t predict how ideas spread through the population. You can study every computer on the internet, but this won’t explain how global information patterns form.

The difficulty lies not in the individual nodes or edges, but in how they combine to create system-level behaviors that are genuinely novel. Scale overwhelms intuition; while you can mentally track relationships between three people, the same intuition fails completely with three million. Small changes can have massive consequences; removing one connection might fragment an entire network, while removing another has no effect at all. This is why network science exists as a distinct field: the traditional reductionist toolkit simply isn’t sufficient for understanding interconnected systems where the connections themselves are the source of complexity!