A Stroll, Seven Bridges, and a Mathematical Revolution

1 Why Was This Puzzle So Hard?

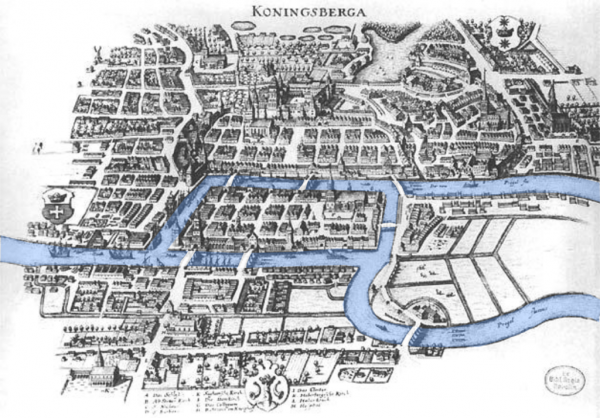

Our story begins not in a lab, but on the streets of an 18th-century Prussian city called Königsberg. It was a city of thinkers—most famously the philosopher Immanuel Kant—but the puzzle that would change mathematics belonged to everyone.

The city was built around two islands in the Pregel River, connected to the mainland and each other by seven distinct bridges. During their Sunday strolls, the citizens amused themselves with a challenge:

Is it possible to design a walk through the city that crosses each of the seven bridges exactly once and return to the starting point?

Go ahead, try it yourself on the map below. Tracing a path with your finger, you’ll soon discover the same frustrating problem the citizens did: you either get stuck, missing a bridge, or you have to cross one twice.

What makes this so difficult? No one could find a path, but more importantly, no one could prove it was impossible. The problem eventually reached the brilliant mathematician Leonhard Euler. His goal was not just to find an answer, but to understand the reason behind the answer.

Before we reveal Euler’s solution, take a moment to be a mathematician yourself. This is how discovery happens. We strongly recommend working through this pen-and-paper worksheet to experience the discovery process.

As you work, ask yourself: - What information is essential? The length of the bridge? The size of the island? - What are the fundamental constraints of the problem? - How can you move from “I can’t find a path” to “A path cannot exist”?

2 A New Way of Seeing: The Power of Abstraction

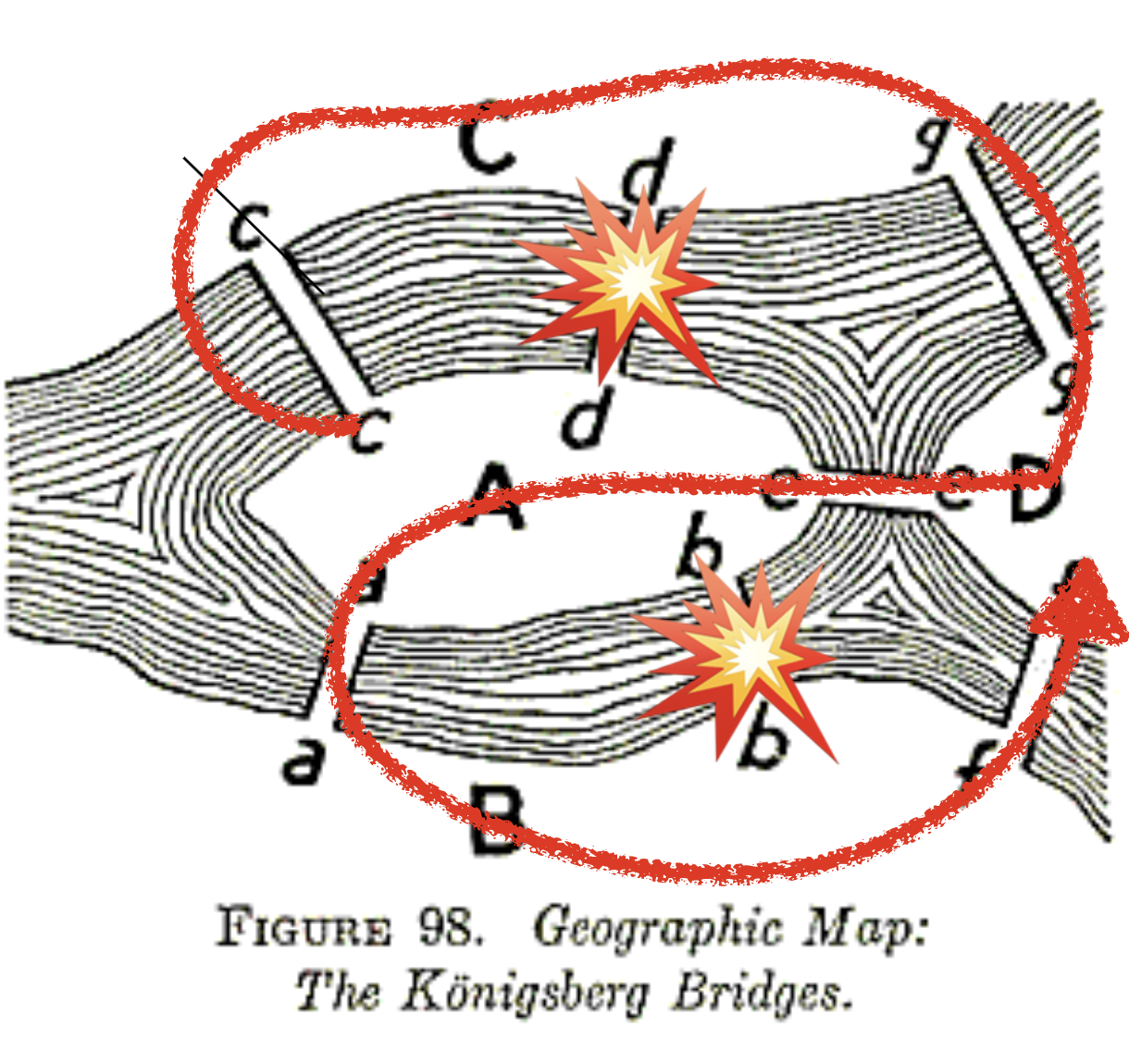

Euler’s genius was to realize that most of the information in the map was a distraction. He performed a radical act of simplification, an approach we now call abstraction.

He stripped the problem down to its skeleton: 1. He turned each of the four distinct landmasses into a simple dot (a node). 2. He turned each of the seven bridges into a simple line connecting the dots (an edge).

This wasn’t just a sketch; it was a new mathematical object. Euler had invented the graph (or network). He had created a new language to talk not about numbers or shapes, but about pure relationships and connectivity.

Leonhard Euler (1707-1783)  One of history’s most prolific mathematicians. Despite losing his sight, he produced nearly half of his life’s work while completely blind.

One of history’s most prolific mathematicians. Despite losing his sight, he produced nearly half of his life’s work while completely blind.

3 From a Walk to a Proof: The Idea of Degree

With this new, simplified representation, Euler could stop thinking about walking and start thinking about rules. He focused on the nodes and asked a crucial question: how does a journey through a node work?

Imagine you are on a walk. Every time you arrive at a landmass, you cross one bridge. Every time you leave, you cross another. This means that for any landmass that is not the start or end of your journey, you must use bridges in pairs: one “in” and one “out.”

This leads to the key insight. Let’s count the number of bridges connected to each landmass. We’ll call this the degree of the node.

The degree of a node is the number of edges connected to it. It is the most fundamental property of a node in a network.

- If a node has an even degree (like 2, 4, or 6), you can always pass through it. For every “in” bridge, there is an “out” bridge.

- If a node has an odd degree (like 1, 3, or 5), it must be special. The “in” and “out” bridges can’t all be paired up. One bridge will be left over. This means an odd-degree node must be the start or the end point of your walk.

A walk can only have one start and one end. Therefore, to cross every bridge, there can be at most two nodes with an odd degree.

The Verdict

Let’s apply this logic to the Königsberg graph:

- North Shore: Degree 3 (Odd)

- South Shore: Degree 3 (Odd)

- Island A: Degree 5 (Odd)

- Island B: Degree 3 (Odd)

All four landmasses have an odd degree! Since a walk can have at most two odd-degree nodes (one for the start, one for the end), the desired walk is mathematically impossible. Euler didn’t just fail to find a path; he proved, with logical certainty, that no such path could ever exist.

A walk that crosses every edge in a graph exactly once (an Eulerian Path) is possible if and only if:

- The graph is connected (you can get from any node to any other).

- And one of these is true:

- Zero nodes have an odd degree. The walk must start and end at the same node (a closed loop, or Eulerian Circuit).

- Exactly two nodes have an odd degree. The walk must start at one of the odd nodes and end at the other.

A Tragic Epilogue

The story of the seven bridges has a sad, ironic twist. During World War II, the city of Königsberg was heavily bombed. Two of the seven bridges were destroyed, changing the layout of the city forever.

With the two bridges gone, the network changed. Two of the landmasses now had an even degree, leaving just two with an odd degree. The impossible puzzle, which had fascinated people for over 200 years, was suddenly “solved” by the destruction of war.

Euler’s solution was far more than fun trivia. It was the beginning of a new field of science. The idea of abstracting a system into nodes and edges is how we now understand our modern world. Every time you rely on a connected system, you are benefiting from the intellectual leap made by Euler over a puzzle about a Sunday stroll!

4 The Vocabulary of Networks

To talk precisely about networks, we need to formalize the language Euler created. Here are the key terms.

Walk, Trail, and Path

| Term | Definition | Analogy: A Road Trip |

|---|---|---|

| Walk | A sequence of nodes where you can repeat both roads (edges) and cities (nodes). | A casual drive where you can go down the same street multiple times. |

| Trail | A walk where you cannot repeat edges, but you can revisit nodes. | A mail route. The carrier can’t cover the same street twice but may pass the same intersection. |

| Path | A walk where you cannot repeat nodes (or edges, by consequence). | A trip visiting a sequence of cities, each one new. |

Cycle and Circuit

A journey that starts and ends at the same place is closed. This gives us two more terms:

| Term | Definition | Analogy: A Round Trip |

|---|---|---|

| Circuit | A trail that starts and ends at the same node. | A scenic drive from your hotel and back, never taking the same road twice. |

| Cycle | A path that starts and ends at the same node. | A perfect loop, like a lap on a racetrack. |

With this vocabulary, we can be more precise about the Königsberg problem.

- An Eulerian Trail/Path is a trail that uses every edge in the graph.

- An Eulerian Circuit/Cycle is a circuit that uses every edge in the graph.

The citizens were looking for an Eulerian circuit. Euler proved that to have one, all nodes must have an even degree.

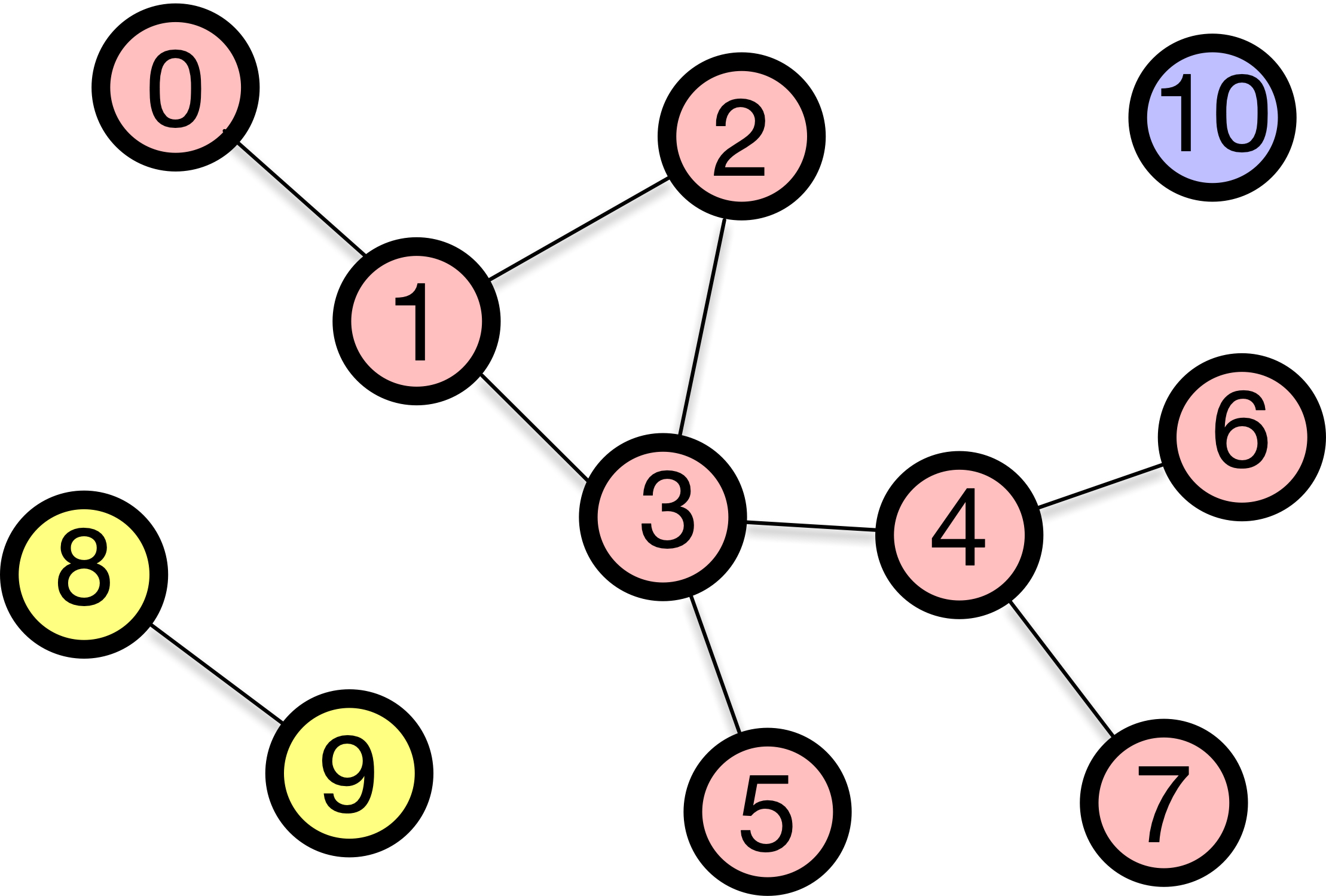

Network Connectivity

Euler’s theorem only applies if the graph is connected. If you can’t get from one part of the network to another, then a single walk can’t possibly cover all the edges.

- A graph is connected if there is a path between any two nodes.

- A disconnected graph is made of two or more separate “islands” of nodes, called connected components.

Connectivity in Directed Networks

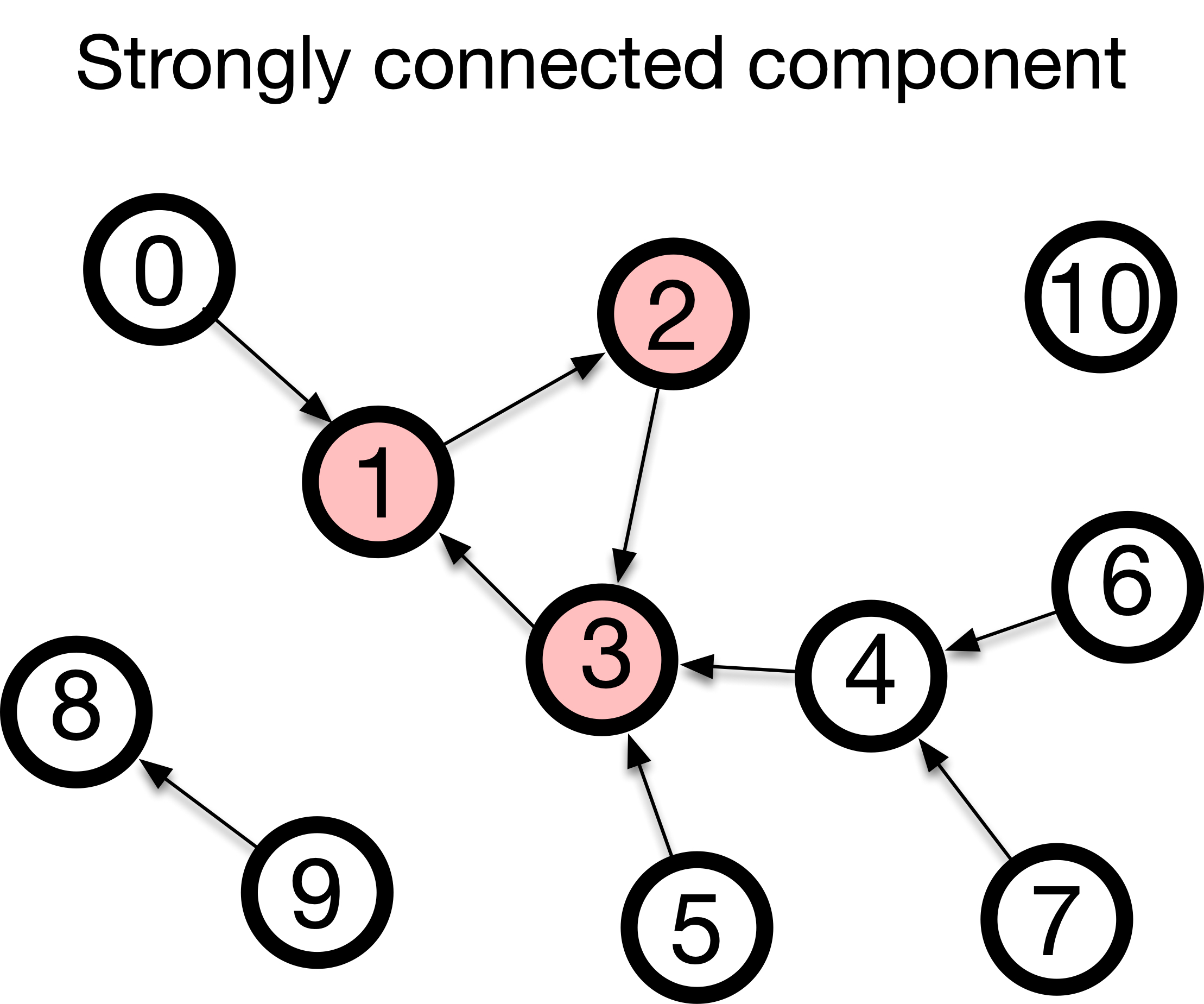

What if edges have a direction, like one-way streets? We call these directed graphs. This introduces two flavors of connectivity:

- Weakly Connected: The graph would be connected if you ignored the edge directions. You can get from A to B, but maybe not from B to A.

- Strongly Connected: There is a directed path from every node to every other node. No matter where you start, you can get anywhere else by following the arrows.