Teaching computers how to understand words#

Imagine trying to explain the meaning of words to someone who only understands numbers. This is exactly the challenge we face when teaching computers to process text. Just as we need to translate between languages, we need to translate between the world of human language and the world of computer numbers. This translation process has evolved dramatically over time, becoming increasingly sophisticated in its ability to capture the nuances of meaning.

One-Hot Encoding: The First Step#

The simplest approach to this translation challenge is one-hot encoding, akin to giving each word its own unique light switch in a vast room of switches. When representing a word, we turn on its switch and leave all others off. For example, in a tiny vocabulary of just three words {cat, dog, fish}:

‘cat’ becomes [1, 0, 0]

‘dog’ becomes [0, 1, 0]

‘fish’ becomes [0, 0, 1]

While simple, this approach has a fundamental flaw: it suggests that all words are equally different from each other. In this representation, ‘cat’ is just as different from ‘dog’ as it is from ‘algorithm’ - something we know isn’t true in real language use.

Distributional Hypothesis#

What is missing in one-hot encoding is the notion of context.

One associates cat with dog because they have similar context, while cat is more different from fish than dog because they are in different contexts.

This is the core idea of the distributional hypothesis.

In a nutshell, the distributional hypothesis states that:

Words that frequently appear together in text (co-occur) are likely to be semantically related

The meaning of a word can be inferred by examining the distribution of other words around it

Similar words will have similar distributions of surrounding context words

This hypothesis forms the theoretical foundation for many modern word embedding techniques.

Note

The idea that words can be understood by their context is captured by the famous linguistic principle: “You shall know a word by the company it keeps” [1]. This principle suggests that the meaning of a word is not inherent to the word itself, but rather emerges from how it is used alongside other words.

Tip

The ancient Buddhist concept of Apoha, developed by Dignāga in the 5th-6th century CE, shares similarities with modern distributional semantics. According to Apoha theory, we understand concepts by distinguishing what they are not - for example, we know what a “cow” is by recognizing everything that is not a cow. This mirrors how modern word embeddings define words through their relationships and contrasts with other words, showing how both ancient philosophy and contemporary linguistics recognize that meaning emerges from relationships between concepts.

TF-IDF: A Simple but Powerful Word Embedding Technique#

Distributional Hypothesis#

What is missing in one-hot encoding is the notion of context. One associates cat with dog because they have similar context, while cat is more different from fish than dog because they are in different contexts. This is the core idea of the distributional hypothesis.

In a nutshell, the distributional hypothesis states that we can understand the meaning of a word by examining the context in which it appears. Just as you might understand a person by the company they keep, we can understand a word by the words that surround it. This principle suggests that words appearing in similar contexts likely have similar meanings.

Note

The idea that words can be understood by their context is captured by the famous linguistic principle: “You shall know a word by the company it keeps” [1]. This principle suggests that the meaning of a word is not inherent to the word itself, but rather emerges from how it is used alongside other words.

TF-IDF: Words as Patterns of Usage#

The distributional hypothesis leads us to an important question: How can we capture these contextual patterns mathematically? More specifically, what is a good unit of “context”? A natural choice is to let the document be the unit of context. The distributional hypothesis suggests that words that frequently appear in the same documents are likely to be semantically related.

First Attempt: Word-Document Count Matrix#

Let’s try to organize this information systematically. Imagine creating a giant table where:

Each row represents a word

Each column represents a document

Each cell contains the count of how often that word appears in that document

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# Sample documents

documents = [

"The cat chases mice in the garden",

"The dog chases cats in the park",

"Mice eat cheese in the house",

"The cat and dog play in the garden"

]

# Create word count matrix

vectorizer = CountVectorizer()

count_matrix = vectorizer.fit_transform(documents)

words = vectorizer.get_feature_names_out()

# Display as a table

df = pd.DataFrame(count_matrix.toarray(), columns=words)

df.style.background_gradient(cmap='cividis', axis = None).set_caption("Word-Document Count Matrix")

| and | cat | cats | chases | cheese | dog | eat | garden | house | in | mice | park | play | the | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

Note

This matrix is our first attempt at a distributed representation - each word is represented not by a single number, but by its pattern of appearances across all documents.

The Problem with Raw Counts#

Looking at our word-document matrix, something seems off. Words like “the” and “in” appear frequently in almost every document. Are these words really the most important for understanding document meaning? Let’s see what happens if we count how often each word appears across all documents:

word_counts = df.sum(axis=0)

word_counts_df = pd.DataFrame(word_counts, columns=["count"]).T

word_counts_df.style.background_gradient(cmap='cividis', axis = None).set_caption("Total appearances of each word")

| and | cat | cats | chases | cheese | dog | eat | garden | house | in | mice | park | play | the | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

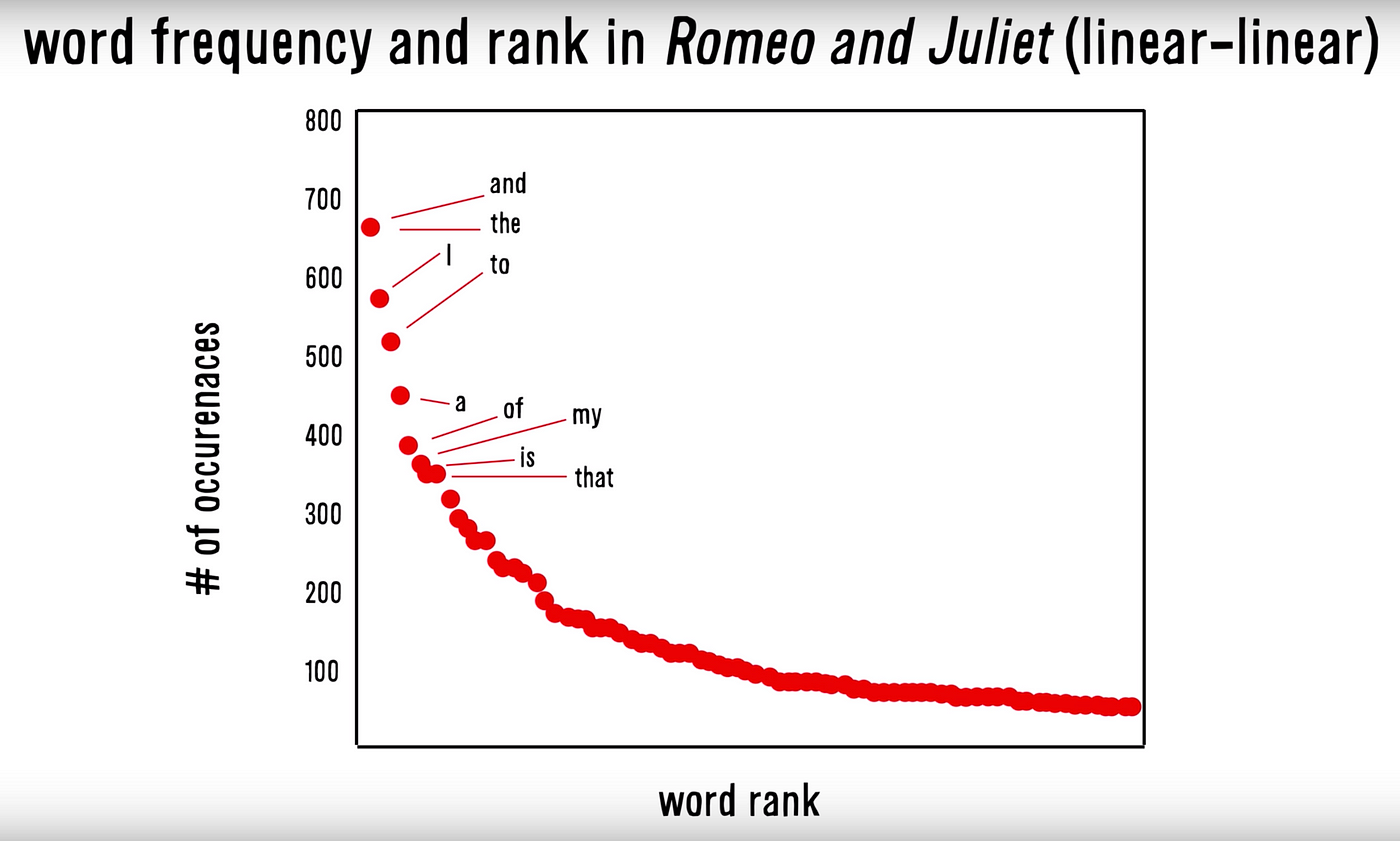

Note

This pattern, where a few words appear very frequently while most words appear rarely, is known as Zipf’s Law. It’s a fundamental property of natural language.

We’ve discovered two problems with raw word counts:

Common words like “the” and “in” dominate the counts, but they tell us little about document content

Raw frequencies don’t tell us how unique or informative a word is across documents

Think about it: if a word appears frequently in one document but rarely in others (like “cheese” in our example), it’s probably more informative about that document’s content than a word that appears equally frequently in all documents (like “the”).

This realization leads us to two important questions:

How can we normalize word frequencies within each document to account for document length?

How can we adjust these frequencies to give more weight to words that are unique to specific documents?

TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) provides elegant solutions to both questions. Let’s see how it works in the next section.

The Need for Normalization#

TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) offers our first practical glimpse into representing words as distributed patterns rather than isolated units.

The TF-IDF score for a word \(t\) in document \(d\) combines two components:

\(\text{TF-IDF}(t,d) = \text{TF}(t,d) \times \text{IDF}(t)\)

where:

\(\text{TF}(t,d) = \dfrac{\text{count of term }t\text{ in document }d}{\text{total number of terms in document }d}\)

\(\text{IDF}(t) = \log\left(\dfrac{\text{total number of documents}}{\text{number of documents containing term }t}\right)\)

Note

Unlike one-hot encoding where each word is represented by a single position, TF-IDF represents each word through its pattern of occurrence across all documents. This distributed nature allows TF-IDF to capture semantic relationships: words that appear in similar documents will have similar patterns of TF-IDF scores.

Let’s see this distributed representation in action: First, let us consider a simple example with 5 documents about animals.

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Sample documents about animals

documents = [

"Cats chase mice in the garden",

"Dogs chase cats in the park",

"Mice eat cheese in the house",

"Pets like dogs and cats need care",

"Wild animals hunt in nature"

]

Second, we will split each document into words and create a vocabulary. This process is called tokenization.

tokens = []

vocab = set()

for doc in documents:

tokens_in_doc = doc.lower().split()

tokens.append(tokens_in_doc)

vocab.update(tokens_in_doc)

# create a dictionary that maps each word to a unique index

word_to_idx = {word: i for i, word in enumerate(vocab)}

Third, we will count how many times each word appears in each document. We begin by creating a placeholder matrix tf_matrix to store the counts.

# Calculate term frequencies for each document

n_docs = len(documents) # number of documents

n_terms = len(vocab) # number of words

# This is a matrix of zeros

# with the number of rows equal to the number of words

# and the number of columns equal to the number of documents

tf_matrix = np.zeros((n_terms, n_docs))

print(tf_matrix)

[[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]]

And then we count how many times each word appears in each document.

for doc_idx, tokens_in_doc in enumerate(tokens):

for word in tokens_in_doc:

term_idx = word_to_idx[word]

tf_matrix[term_idx, doc_idx] += 1

print(tf_matrix)

[[0. 0. 1. 0. 0.]

[1. 1. 0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0.]

[1. 1. 1. 0. 1.]

[0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. 0. 0.]

[1. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0.]

[1. 0. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 1.]

[0. 0. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 1.]

[1. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0.]

[0. 1. 0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 1.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 1.]

[1. 1. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0.]]

Fourth, we calculate the IDF for each word. IDF is defined as the logarithm of the inverse document frequency. Document frequency is the number of documents that contain the word. Note that, if a word appears multiple times in the same document, it should only be counted once!

# Calculate IDF for each term

# let's use tf_matrix to calculate the document frequency

doc_freq = np.zeros(n_terms)

# Go through each word

for term_idx in range(n_terms):

# For each word, go through each document

for doc_idx in range(n_docs):

# If the word appears in the document, increment the document frequency

if tf_matrix[term_idx, doc_idx] > 0:

doc_freq[term_idx] += 1

idf = np.log(n_docs / doc_freq)

Next, we calculate the TF-IDF matrix. tf_matrix is a matrix of n_terms by n_docs, and idf is a vector of length n_terms. Remind that the tf-idf is given by

\( \text{TF-IDF}(t,d) = \text{TF}(t,d) \times \text{IDF}(t) \)

A naive way to do this (albeit not efficient) is to perform this using for loops

# Calculate TF-IDF matrix

tfidf_matrix = np.zeros((n_terms, n_docs))

for term_idx in range(n_terms):

for doc_idx in range(n_docs):

tfidf_matrix[term_idx, doc_idx] = tf_matrix[term_idx, doc_idx] * idf[term_idx]

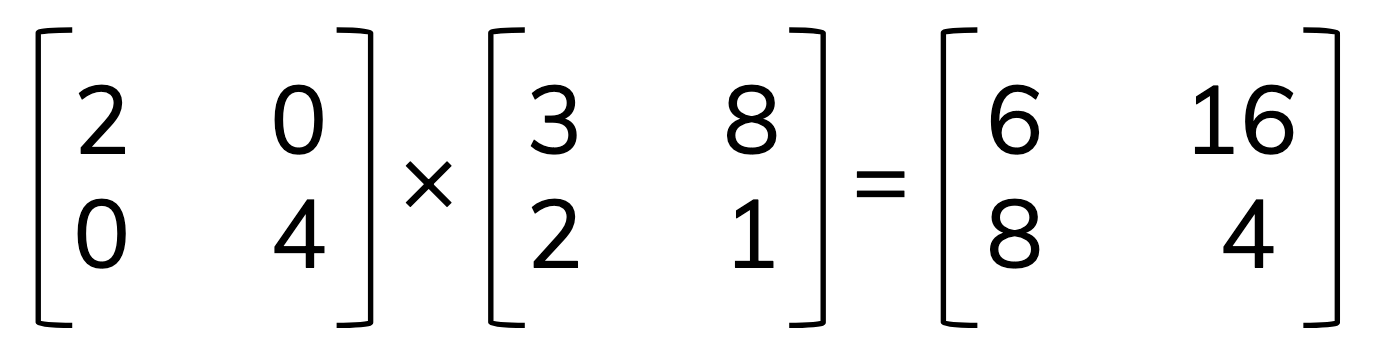

A more efficient way is to use matrix multiplication.

tfidf_matrix = np.diag(idf) @ tf_matrix

where np.diag(idf) creates a diagonal matrix with idf on the diagonal.

Tip

Consider a diagonal matrix as a tool to scale the rows/columns of a matrix. If we multiple a diagonal matrix from the left, we scale the rows of the matrix. If we multiple a diagonal matrix from the right, we scale the columns of the matrix.

A more efficient way is to use einsum, which is a powerful function for performing Einstein summation convention on arrays.

tfidf_matrix = np.einsum('ij,i->ij', tf_matrix, idf)

Tip

einsum provides a concise way to express complex array manipulations and can often lead to more efficient computations. Here is a concise description of how einsum works A basic introduction to NumPy’s einsum

The general form of einsum is np.einsum(subscripts, *operands), where:

subscriptsis a string specifying the subscripts for summation as comma-separated list of subscript labelsoperandsare the input arrays

In our case, 'ij,i->ij' means:

Take the first array

tf_matrixwith dimensionsi,jTake the second array

idfwith dimensioniMultiply each row

joftf_matrixby the corresponding elementiofidfOutput has same dimensions

i,jas input

Now, we have the TF-IDF matrix as follows:

print(tfidf_matrix)

[[0. 0. 1.60943791 0. 0. ]

[0.51082562 0.51082562 0. 0.51082562 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 1.60943791 0. ]

[0.22314355 0.22314355 0.22314355 0. 0.22314355]

[0. 1.60943791 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 1.60943791 0. 0. ]

[1.60943791 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 1.60943791 0. ]

[0.91629073 0. 0.91629073 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 1.60943791]

[0. 0. 1.60943791 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 1.60943791]

[0.91629073 0.91629073 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 1.60943791 0. ]

[0. 0.91629073 0. 0.91629073 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 1.60943791 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 1.60943791]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 1.60943791]

[0.51082562 0.51082562 0.51082562 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 1.60943791 0. ]]

Each row of the TF-IDF matrix is our first attempt at a distributed representation of a word. Words that appear together in the same documents frequently will have similar rows.

Just like one-hot encoding, this representation can be high-dimensional, e.g., if we have 10000 documents, each word is represented by a vector of length 10000. One can reduce the dimensionality of the representation using dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., PCA, SVD) while maintaining the structure of the data. This is possible because tf-idf matrix is often low-rank in practice.

Note

TF-IDF matrices are often low-rank because documents naturally group into clusters based on topics or themes. This clustering creates redundancy in the term-document matrix, as many terms are specific to certain clusters and rare in others. Consequently, the TF-IDF matrix can be approximated by a lower-rank matrix. This low-rank nature is useful for applications like dimensionality reduction and topic modeling, as it simplifies data visualization and analysis.

Let us apply PCA to reduce the dimensionality of the tf-idf matrix.

reducer = PCA(n_components=2)

xy = reducer.fit_transform(tfidf_matrix)

Let’s visualize the result using Bokeh.

from bokeh.plotting import figure, show, output_notebook

from bokeh.models import ColumnDataSource

from bokeh.io import push_notebook

from bokeh.plotting import figure, show

from bokeh.io import output_notebook

from bokeh.models import ColumnDataSource, HoverTool

output_notebook()

# Prepare data for Bokeh

source = ColumnDataSource(data=dict(

x=xy[:, 0],

y=xy[:, 1],

text_x=xy[:, 0] + np.random.randn(n_terms) * 0.02,

text_y=xy[:, 1] + np.random.randn(n_terms) * 0.02,

term=list(word_to_idx.keys())

))

p = figure(title="Node Embeddings from Word2Vec", x_axis_label="X", y_axis_label="Y")

p.scatter('x', 'y', source=source, line_color="black", size = 30)

# Add labels to the points

p.text(x='text_x', y='text_y', text='term', source=source, text_font_size="10pt", text_baseline="middle", text_align="center")

show(p)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[13], line 1

----> 1 from bokeh.plotting import figure, show, output_notebook

2 from bokeh.models import ColumnDataSource

3 from bokeh.io import push_notebook

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'bokeh'

The power of TF-IDF lies in its ability to transform the distributional hypothesis into a practical mathematical framework. By representing words through their patterns of usage across documents, TF-IDF creates a distributed representation where semantic relationships emerge naturally from the data.

However, TF-IDF has its limitations. It only captures word-document relationships, missing out on the rich word-word relationships that occur within documents. This limitation led researchers to develop more sophisticated techniques like word2vec, which we’ll explore in the next section.