Appendix: Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer (T5)#

T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) is a transformer-based model introduced by Google in 2020. It represents a milestone in NLP by providing a unified approach to handle diverse tasks like translation, summarization, classification, and question answering. T5 embodies the best practices in transformer architecture design and showcases the state of NLP technology at the time of its release. Understanding T5 provides a good starting point into effective transformer model design for NLP applications. This note covers only the essennce, and interested readers are encouraged to read the original paper [1].

What is T5?#

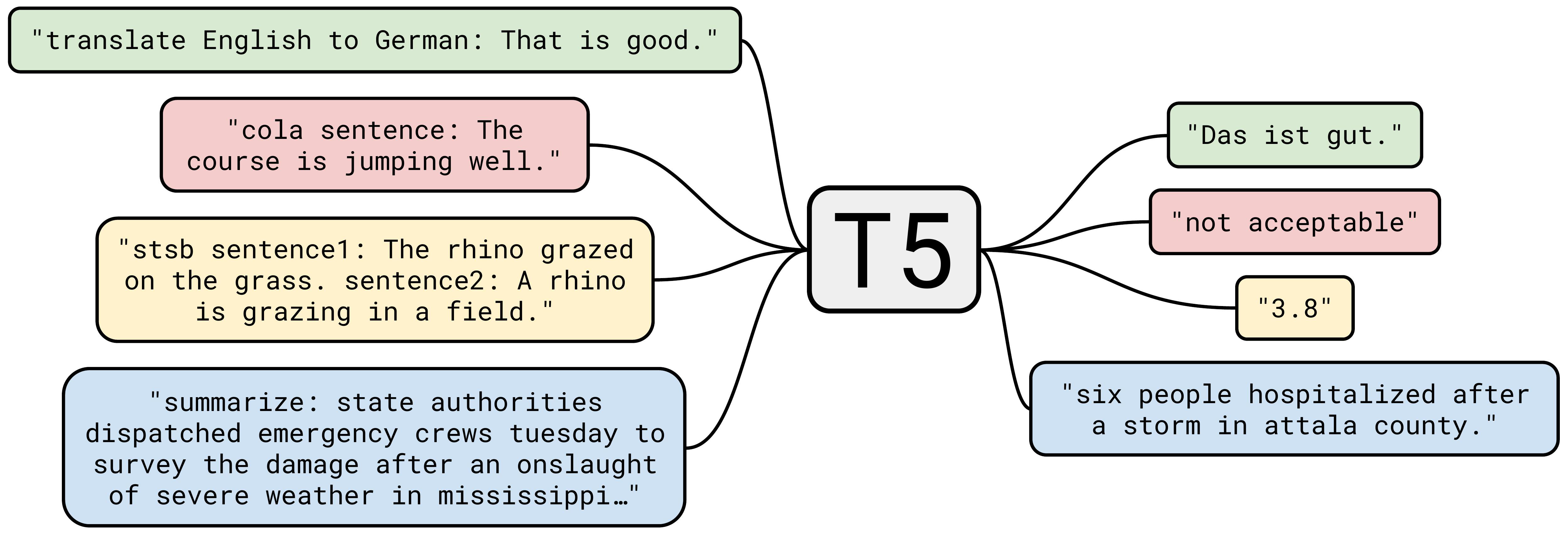

A core idea of T5 is that most NLP tasks can be formulated as converting input text into output text. For example, translation becomes “translate English to German: [text]”, summarization becomes “summarize: [text]”, and classification becomes “classify: [text]”.

Fig. 42 Many NLP tasks such as translation, summarization, classification, and question answering can be formulated as converting input text into output text.#

The rise of transformer models has led to diverse approaches in NLP. Different models such as BERT and GPT were developed with specialized architectures and pre-training objectives. For example, BERT uses bidirectional attention for language understanding tasks, while GPT uses unidirectional attention for text generation. However, these models become so diverse that it became challenging to determine which architectural choices and training methods were most effective. T5 addresses this by providing a unified framework that enables direct comparison between different transformer model designs and helps identify the key factors driving their success.

Comparison of practices#

The original paper of T5 [1] is like a review paper that summarizes the effective practices for transformer models. The authors compared various practices and used the most effective ones to form T5. This note covers only the overview of the practices. Interested readers are encouraged to read the original paper.

Model Architecture#

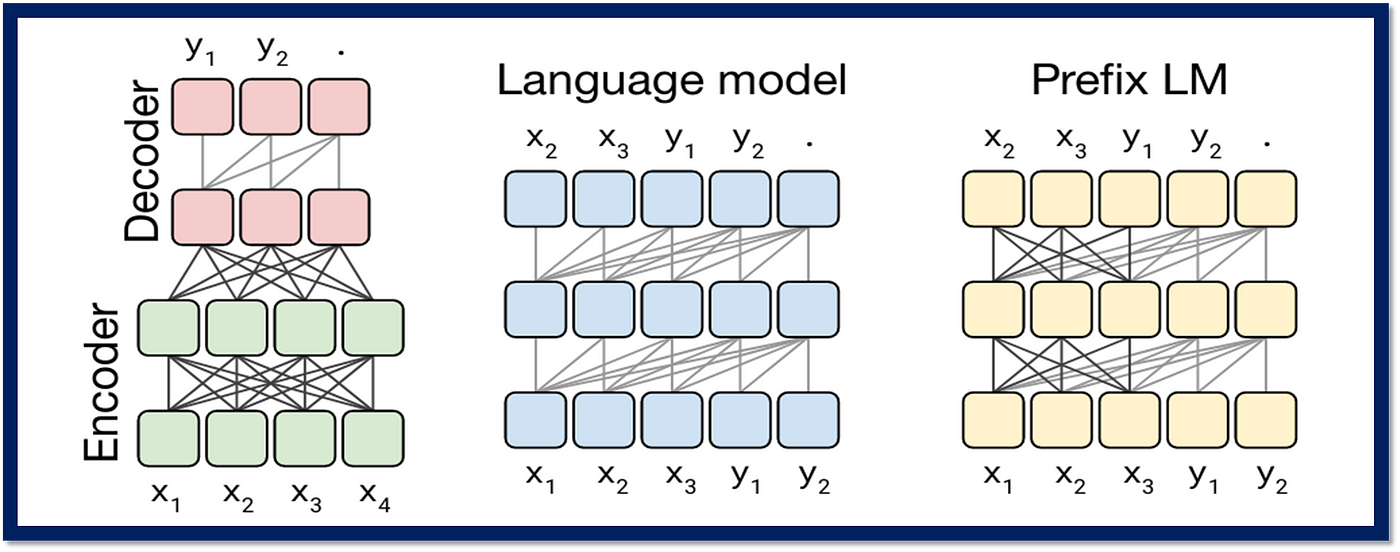

Three architectures have been widely used for language models:

Fig. 43 Three main architectures for language models.#

Encoder-Decoder#

The encoder-decoder architecture largely follows the design proposed in “Attention is All You Need”. The encoder processes the input sequence using self-attention to create contextual representations, while the decoder generates the output sequence using both self-attention and cross-attention to the encoder’s representations.

Note

T5 handles positional information differently from the original Transformer. While the original Transformer added absolute position encodings to input embeddings (marking each token’s exact position), T5 uses relative position embeddings. These embeddings represent the relative distance between tokens in the self-attention mechanism, rather than their absolute positions. The relative position information is incorporated as a bias term when computing attention weights, and while each attention head uses different embeddings, they are shared across all layers of the model.

Language Model#

In a Language Model, only the Decoder of the Encoder-Decoder architecture is used. It generates output recursively by sampling words from the output of step \(i\) and using them as input for step \(i+1\). Models such as GPT fall into this type.

Prefix LM#

When using a Language Model in a “Text-to-Text” context, one drawback is that it can only predict the next token based on the sequence of tokens from the beginning to the current position, which means it cannot learn bidirectional dependencies such as those learned by BERT. A Prefix LM addresses this by cleverly designing the attention masking: it allows bidirectional visibility for the input text portion (=Prefix) and unidirectional visibility for the output text portion. For example, in the case of English-French translation:

The model can see all tokens in the input portion bidirectionally, but can only see previous tokens in the output portion, ensuring proper translation generation.

The prefix-LM is implemented by attention masking, where the input tokens can attent to all tokens in the input portion bidirectionally, but the output tokens can only attend to previous tokens in the output portion (the right most part of the figure below).

Fig. 44 Attention masking for Prefix LM vs Causal LM. Image from Brief Review — Unified Language Model Pre-training for Natural Language Understanding and Generation | by Sik-Ho Tsang | Medium#

Pre-training Objectives#

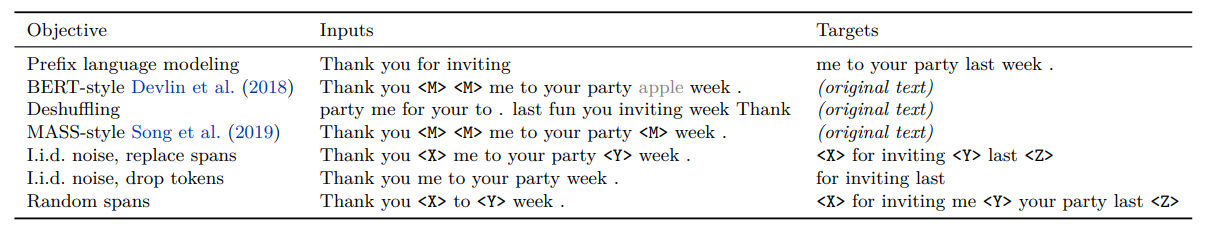

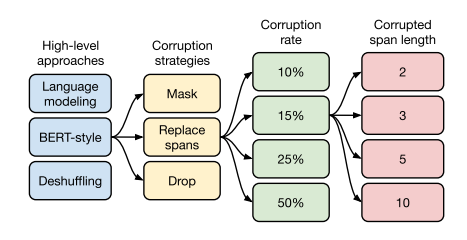

Three methods were considered for pre-training objectives: Prefix language modeling, Masked language modeling, and Deshuffling. For Masked language modeling, several variations were further explored. Table 3 in the paper clearly illustrates how each objective function processes the text.

Fig. 45 Table 3 from the original paper.#

Prefix language modeling: This is essentially a standard language model where the beginning of the text is given, and the model predicts what follows.

BERT-Style: This is BERT’s pre-training method. It masks 15% of tokens, replacing 90% of these with

"<M>"and the remaining 10% with random tokens (shown as grey “apple” in the figure), then tries to recover the original text.Deshuffling: This involves rearranging the token order and having the model restore the original text.

Among these three, “BERT-Style” proved most effective. The following variations build upon “BERT-Style,” aiming to speed up and lighten pre-training:

i.i.d noise, mask tokens: This removes the random token replacement (grey “apple”) from BERT-Style.

i.i.d noise, replace spans: This replaces consecutive masked tokens (masked spans) with single special tokens (

"<X>"or"<Y>"), then predicts what these special tokens represent.i.i.d noise, drop tokens: This simply removes the masked portions and predicts what was deleted.

Random spans: Since word-level masking rarely creates consecutive masked sections, this approach specifies both the percentage of tokens to mask and the number of masked spans. For example, with 500 tokens, 15% masking rate, and 25 masked spans, the average span length would be 3 (\(500 \times 0.15 / 25 = 3\)).

Experimental results showed that Random spans with a 15% masking rate and average span length of 3 performed best.

Pre-training Datasets#

Google created a massive dataset called the Colossal Clean Crawled Corpus (C4). While Common Crawl 12 exists as a petabyte-scale corpus collected by crawling web servers worldwide, with 20TB of data being released monthly (!), Common Crawl still contains non-natural language content, error messages, menus, duplicate text, and source code, even though markup has been removed. C4 was created by applying various cleaning processes to one month of Common Crawl data. The data size is 745GB, which is 46 times larger than the English Wikipedia.

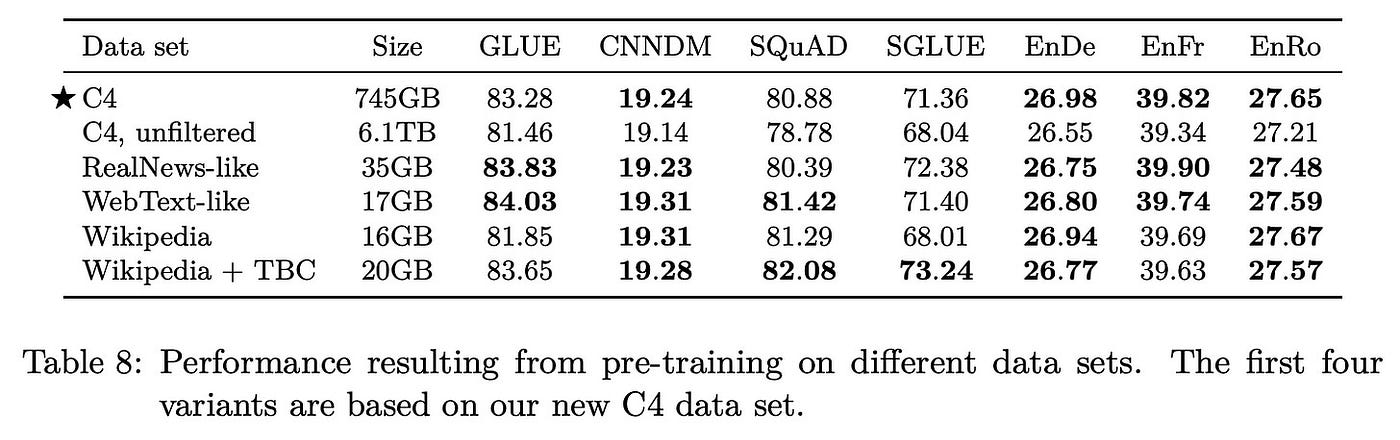

Table 8 in the paper shows comparison results across six datasets including C4.

Fig. 46 Table 8 from the original paper.#

The compared datasets are as follows (simplified for brevity):

C4: A dataset created by applying various cleaning processes to Common Crawl.

C4, unfiltered: C4 with all filtering processes except “English” removed.

RealNews-like: C4 with additional processing to extract only news article content.

WebText-like: Created by applying C4-like cleaning processes to 12 months of Common Crawl and extracting only content that received 3 or more upvotes on Reddit.

Wikipedia: English Wikipedia data from Tensorflow Datasets.

Wikipedia+TBC: Since Wikipedia’s content domain is limited to encyclopedic content, this combines it with Toronto Books Corpus (TBC) data from various ebooks.

While C4 might not seem impressive at first glance, the paper points out:

Looking at “C4, unfiltered” results shows that data quality significantly impacts results.

Results from “Wikipedia+TBC”, “RealNews-like”, and “Wikipedia” indicate that pre-training on datasets matching the downstream task domain improves accuracy

Note

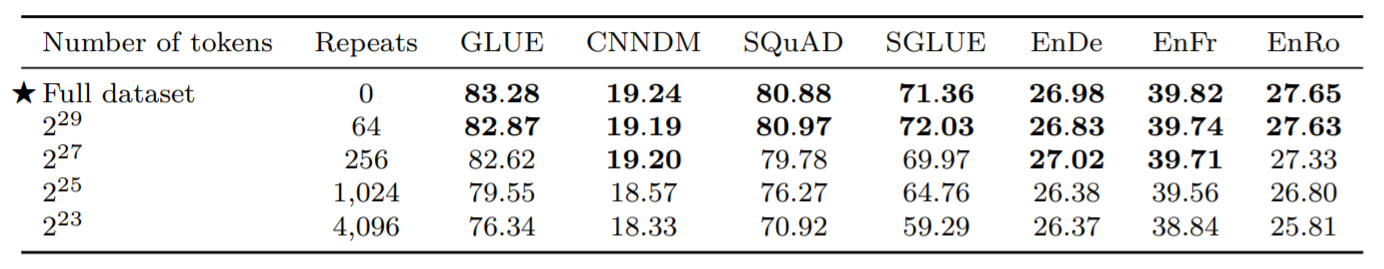

Although there’s a “Size” column in the table, note that this comparison standardizes pre-training learning tokens to \(2^{35}\). This means pre-training does not complete one full pass through their datasets, while “Wikipedia” goes through multiple passes (since it is smaller than \(2^{35}\) tokens). When taking multiple passes, the accuracy tends to decrease compared to that of one pass with the same amount of data, as illustrated in the figure below.

Fig. 47 Results from training with \(2^{35}\) tokens on different-sized datasets. Since the number of training tokens is fixed, as the data volume decreases, the number of passes during training increases. While accuracy decreases as the number of pre-training passes increases, there isn’t much significant decline until around \(2^{29}\) (approximately 540 million) tokens.#

Training Details#

Fine-tuning#

Several fine-tuning methods were compared, with “All parameters” proving to be the best:

All parameters: Updates all parameters during fine-tuning.

Adapter layers: Inserts adapter layers (dense-ReLU-dense blocks) at the end of each Transformer block. During fine-tuning, only updates the adapter layer and layer normalization parameters. Multiple dense layer dimensions were compared.

Gradual unfreezing: Initially only updates parameters of the final stack layer during fine-tuning, gradually expanding parameter updates toward the front layers as training progresses, eventually updating all parameters.

Multi-task Learning#

Multi-task learning trains multiple tasks simultaneously to enable a single model to solve multiple tasks. Since all tasks in T5 use the “Text-to-Text” format, it becomes a question of how to mix learning data from multiple tasks. The paper compares three strategies, though none performed as well as fine-tuning:

Examples-proportional mixing: Samples training data with probability proportional to each task’s dataset size. Sets a limit to control the influence of tasks with extremely large data (i.e., pre-training tasks). Multiple limit parameters were compared.

Temperature-scaled mixing: Mixes tasks by normalizing each task’s sample count raised to 1/T power. Equivalent to “Examples-proportional mixing” when T=1, approaches “Equal mixing” as T increases. Multiple T values were compared.

Equal mixing: Samples training data from each task with equal probability.

They also tried fine-tuning each task after multi-task pre-training, but this too fell short of pre-training + fine-tuning performance.

Model Size#

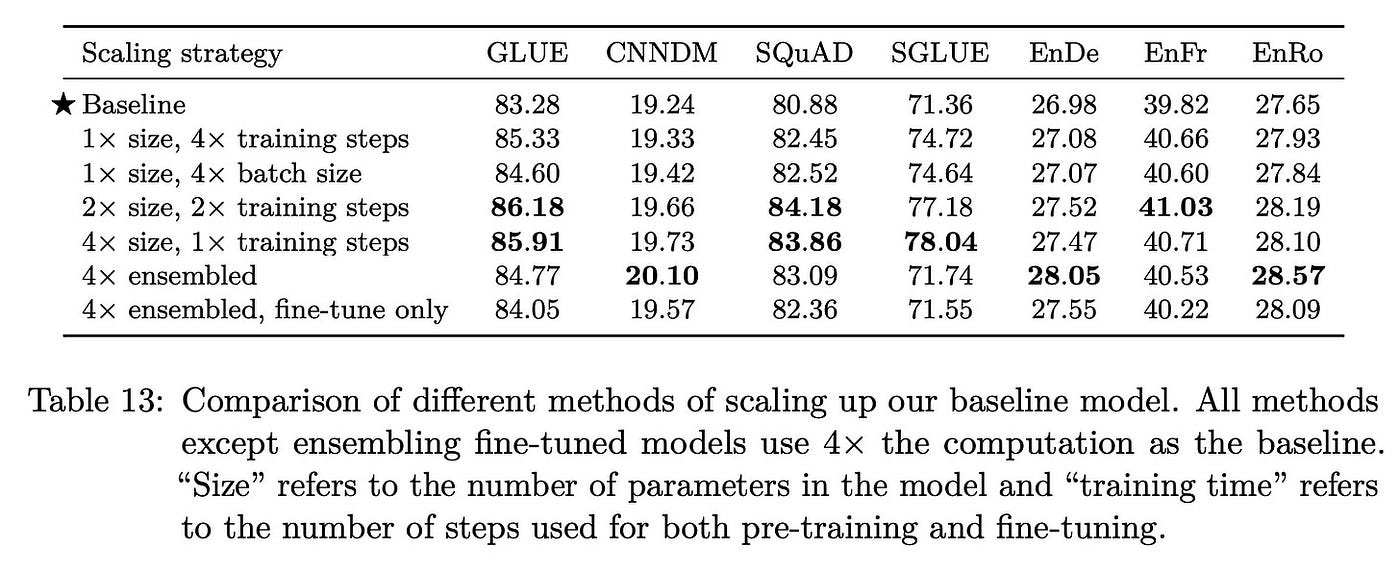

Fig. 48 Table 13 from the original paper.#

The paper explores different model configurations that each use approximately 4 times more computational resources than the baseline model. These variations include training the baseline model for 4 times as many steps, using 4 times larger batch sizes, doubling both model size and training steps, quadrupling the model size while keeping training steps constant, and creating ensembles of multiple models.

For the larger models (2x and 4x size), the researchers used configurations similar to BERT-LARGE, with 16 and 32 transformer layers respectively. When increasing training steps, the model was exposed to more diverse data since the baseline training (using 2³⁵ tokens) only covered a portion of the C4 dataset.

The results showed that all configurations improved upon the baseline, with increasing model size being particularly effective. Interestingly, quadrupling the model size while keeping the same amount of training data still led to better performance, contrary to the expectation that larger models might need more training data.

Summary of validation experiments#

Based on these investigations, the paper proceeds to a systematic experiments using a model with 11 billion parameters trained on C4. You can see that T5 isn’t so much about inventing new model architectures or methods, but rather combining Transformer technology with the latest trends, objective functions, and learning optimizations.

Fig. 49 Design choices for T5.#