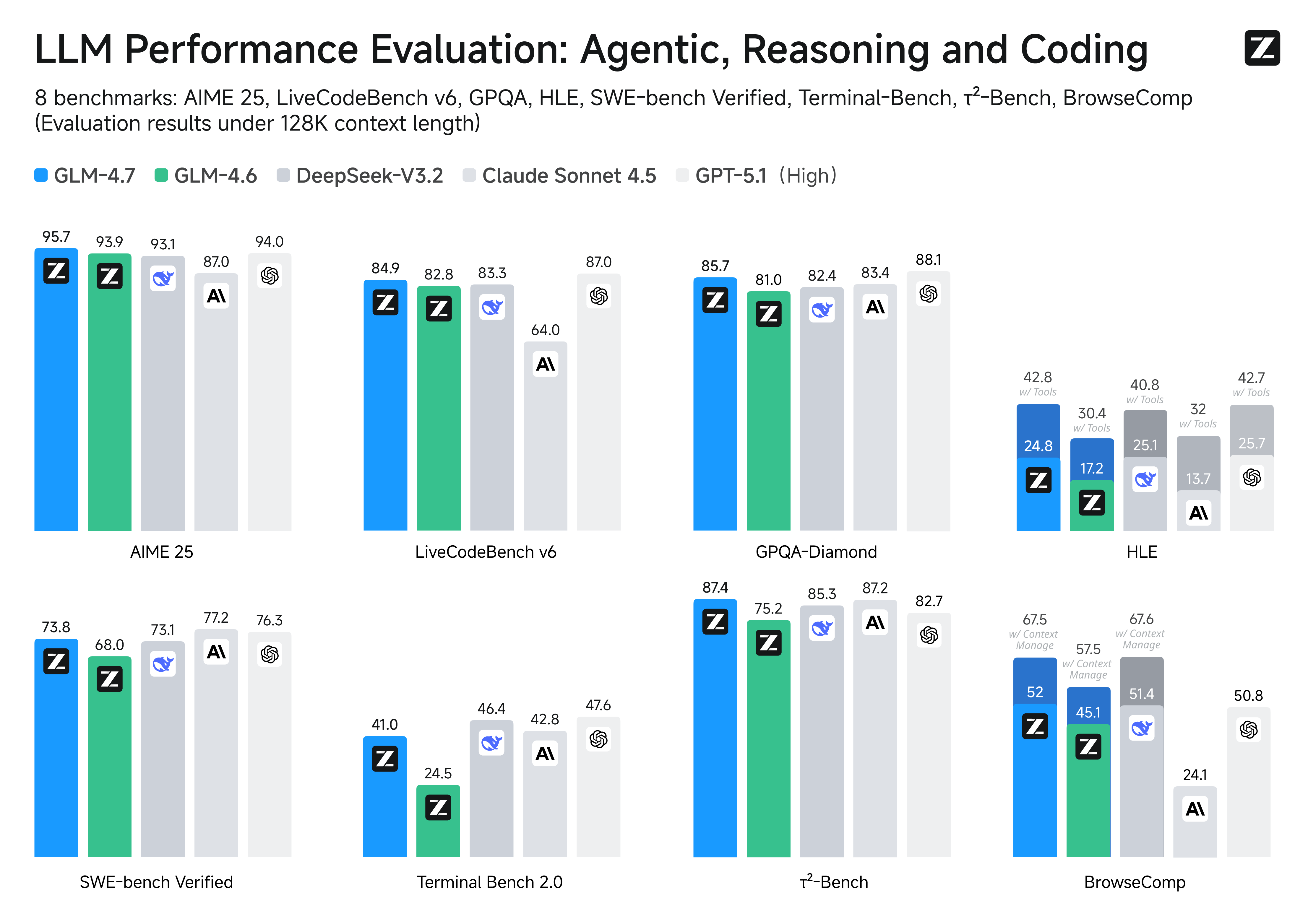

Perception in Data Visualization

This module explores the surprising ways our visual perception can deceive us in data visualization.

You’ll learn:

- How color perception is contextual and subjective, and why systems like RGB, CMYK, and HSL matter for designing effective visualizations.

- What perceptually uniform palettes are and why rainbow colormaps fail to represent data accurately.

- How Gestalt principles (proximity, similarity, enclosure, closure) describe how our brains naturally organize visual information.

- Why we perceive length more accurately than area or volume, and how Steven’s Power Law and Weber’s Law affect chart design.

- How to use preattentive attributes (color, size, shape, orientation) to guide viewer attention and tell compelling data stories.

The Perception of Color

Have you ever argued with someone about the color of an object? Here’s the uncomfortable truth: our visual perception is far from accurate. Let’s talk about the most powerful and complex tool in your visualization arsenal: color. Our perception of color is not absolute but contextual, subjective, and driven by unconscious processes in our brain.

How Color Perception Fools Us

Our visual system tries to maintain color constancy. We perceive a familiar object as having a consistent color regardless of lighting conditions. This is why we recognize a banana as yellow in bright sunlight or in a dim room. This helpful adaptation creates peculiar biases in unfamiliar contexts.

The dress illusion (Figure 1) highlights this perfectly. Our brain makes assumptions about lighting, so some people see the dress as blue and black (assuming bright light) while others see it as white and gold (assuming shadow). The colors are physically the same, but our perception of them is not. What we “see” is not just raw wavelength hitting our eyes but our visual cortex making inferences based on context and prior experience.

Look at Figure 2. We perceive the leaves as green, even though the photograph contains only red, black, and white pixels. Our brain “knows” trees are green, so it fills in the gap.

Encoding Color Objectively

Since perception is subjective, we need objective systems to define color. RGB (Red, Green, Blue) is an additive system for screens where colors are created by adding light (combining all three at full intensity produces white). CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black) is a subtractive system for print where colors are created by subtracting light with ink (combining all three plus black creates black). HSL/HSV (Hue, Saturation, Lightness/Value) are more intuitive systems that align with how humans naturally think about color, where hue is the pure color, saturation is its intensity, and lightness or value is its brightness.

A crucial aspect of color choice is ensuring your visualizations are accessible to everyone, including those with color vision deficiencies (CVD). Roughly 8% of men and 0.5% of women are affected.

First, avoid red-green palettes. The most common form of CVD is difficulty distinguishing between red and green, so this combination creates barriers for a significant portion of your audience.

Second, use perceptually uniform palettes. Tools like ColorBrewer provide palettes specifically designed to be accessible to people with different vision deficiencies.

Third, combine color with other visual cues. Don’t rely solely on color to distinguish data series. Use shape, pattern, or direct labels so your visualization works for everyone, regardless of their color perception.

The Problem with Rainbows: Perceptually Uniform Palettes

What makes a good colormap? A perceptually uniform colormap is one where equal steps in the data are perceived as equal steps in color. The common “rainbow” (or “jet”) colormap fails at this because its brightness changes non-uniformly, creating false boundaries and hiding details.

Figure 3 shows the stark difference. Palettes like Viridis were engineered to have monotonically increasing luminance. This makes them accurate, intuitive, and accessible to everyone.

The Perception of Form and Quantity

Shift your attention from color to shape and structure. Our brains have an innate tendency to see whole forms rather than collections of parts. These Gestalt principles are fundamental to chart design because they describe how visual perception naturally organizes information.

Figure 4 illustrates the core principles. Proximity describes how we group objects that are close together, so placing related data points near each other makes viewers automatically see them as belonging to the same group. Similarity means we group objects that look similar in color, shape, or texture (all bars representing revenue should look the same, distinct from bars representing costs). Enclosure works because we naturally group objects that share a boundary or container, so putting related information inside a box or circle makes viewers perceive it as a unit. Closure and Continuity reflect how we complete incomplete shapes and prefer continuous lines, so even if a line is broken into segments, we see it as one continuous path.

Perceiving Quantity

How accurately can we judge magnitude? Our ability varies dramatically depending on the visual encoding used.

Steven’s Power Law (Figure 5) shows that we are very good at judging length, but poor at judging area and volume, which is why bar charts often work better than pie charts or bubble charts for precise comparisons. What about detecting changes? Weber’s Law suggests that our ability to perceive a change is relative to the magnitude, so we can easily spot a 1-inch difference in a 5-inch line, but that same 1-inch difference disappears in a 50-foot line.

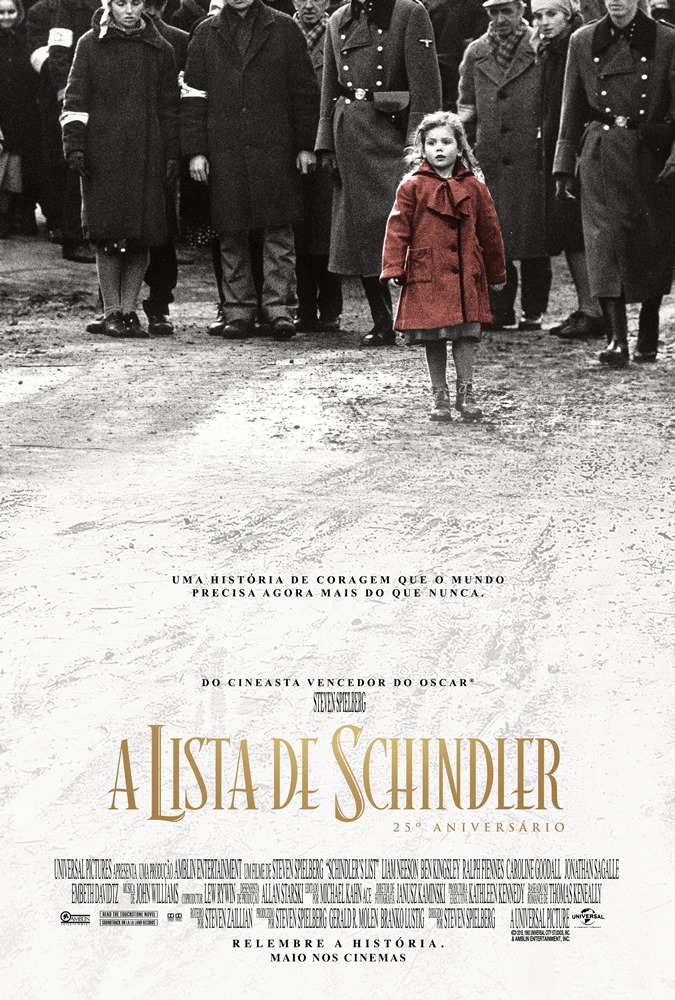

Guiding Attention with Preattentive Attributes

How do you direct the viewer’s eye to what matters most? Preattentive attributes are visual properties that our brains process in milliseconds, before we pay conscious attention. By using them purposefully, you control the visual hierarchy of your chart and tell a story.

Figure 6 is the poster for the movie Schindler’s List (1993). In the poster, all but the girl are wearing dark clothes, while she is wearing a bright red coat. You’d immediately notice her as “red” stands out when surrounded by greys. If all people wore colorful clothes, it would be harder to spot her.

In data visualization, deemphasizing all but the most important elements is equally as effective as highlighting the most important elements. The following is another example that demonstrates this principle.