Part 1: When Boundaries Blur

This section explores the illusion of sharp boundaries in the world around us.

You’ll learn:

- How regional dialects blend gradually rather than dividing cleanly at borders.

- Why generational labels impose arbitrary lines on continuous age cohorts.

- How color perception varies across languages, revealing subjective categorization.

- The Ship of Theseus paradox and what it reveals about object identity.

- Why representation learning offers a way forward by working with continuous variation directly.

The Soft Drink Divide That Isn’t

Have you ever seen a map dividing America into soda, pop, and Coke regions? These maps circulate widely, showing bold lines that separate linguistic territories. In the Northeast and West Coast, carbonated beverages are “soda”. In the Midwest, they’re “pop”. In the South, everything is “Coke”, even if you’re drinking Sprite.

Here’s the problem: this boundary doesn’t exist. Drive from Chicago to Atlanta and you won’t cross a line where everyone suddenly switches from “pop” to “Coke”. Instead, you’ll encounter a gradual transition zone spanning hundreds of miles where St. Louis residents might use both terms while Nashville speakers favor “Coke” but still use “soda”.

The change is gradational, not binary. We draw boundaries because our analytical apparatus demands nodes, and nodes require boundaries. If everything gradually blends into everything else, we cannot construct the graph that lets us study the system. The boundary is not a feature of reality but a feature of our tools.

The Generation Game

This pattern repeats everywhere we look. Consider generational labels like Baby Boomers, Gen X, Millennials, Gen Z. These categories structure entire marketing strategies, political analyses, and cultural narratives.

The Pew Research Center officially defines Millennials as those born between 1981 and 1996. This means someone born on December 31, 1996 is a Millennial, but someone born the next day is Gen Z.

Does this make sense? Is there a meaningful discontinuity between these two people that doesn’t exist between someone born in December 1996 and someone born in January 1996? Of course not. The boundary is arbitrary, chosen for analytical convenience, yet once established, it shapes how we think. We ask “what do Millennials believe?” as if the category reflects a natural kind rather than a statistical convenience. ## Colors

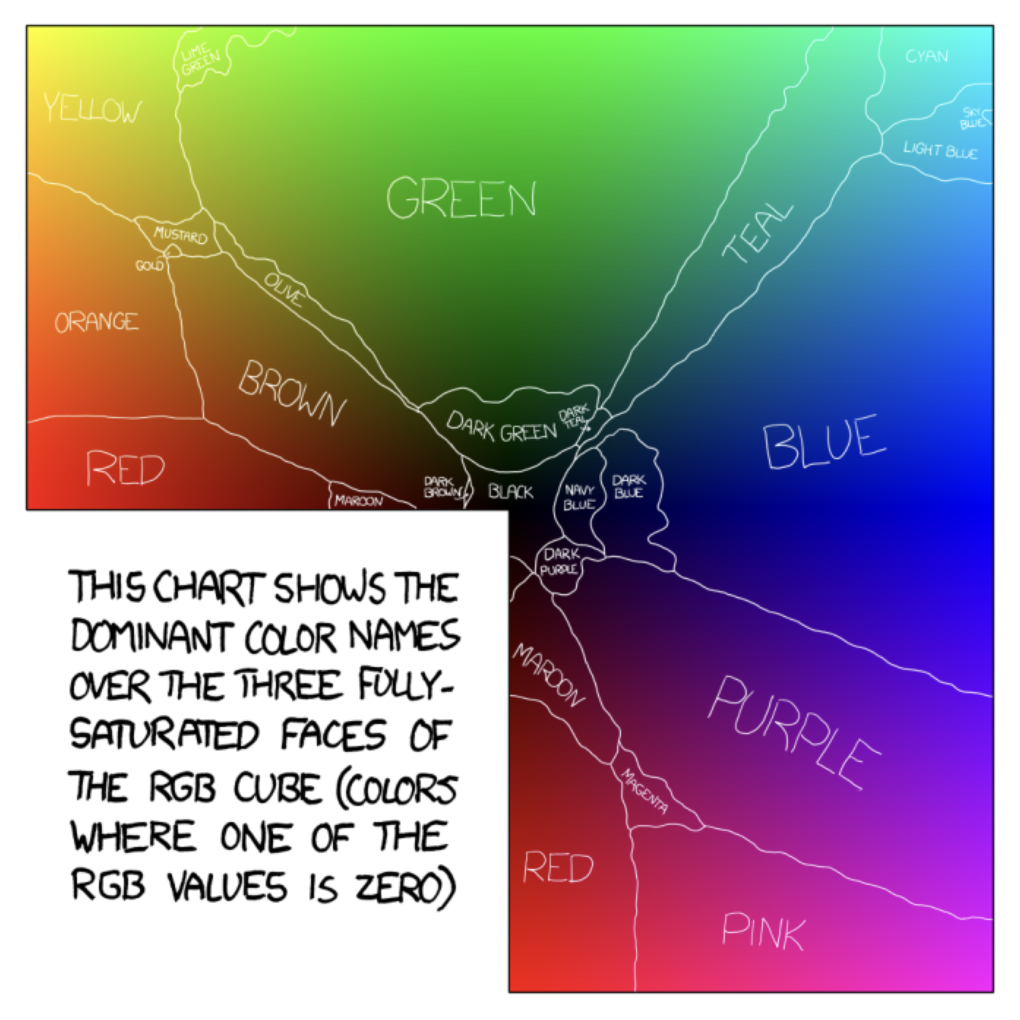

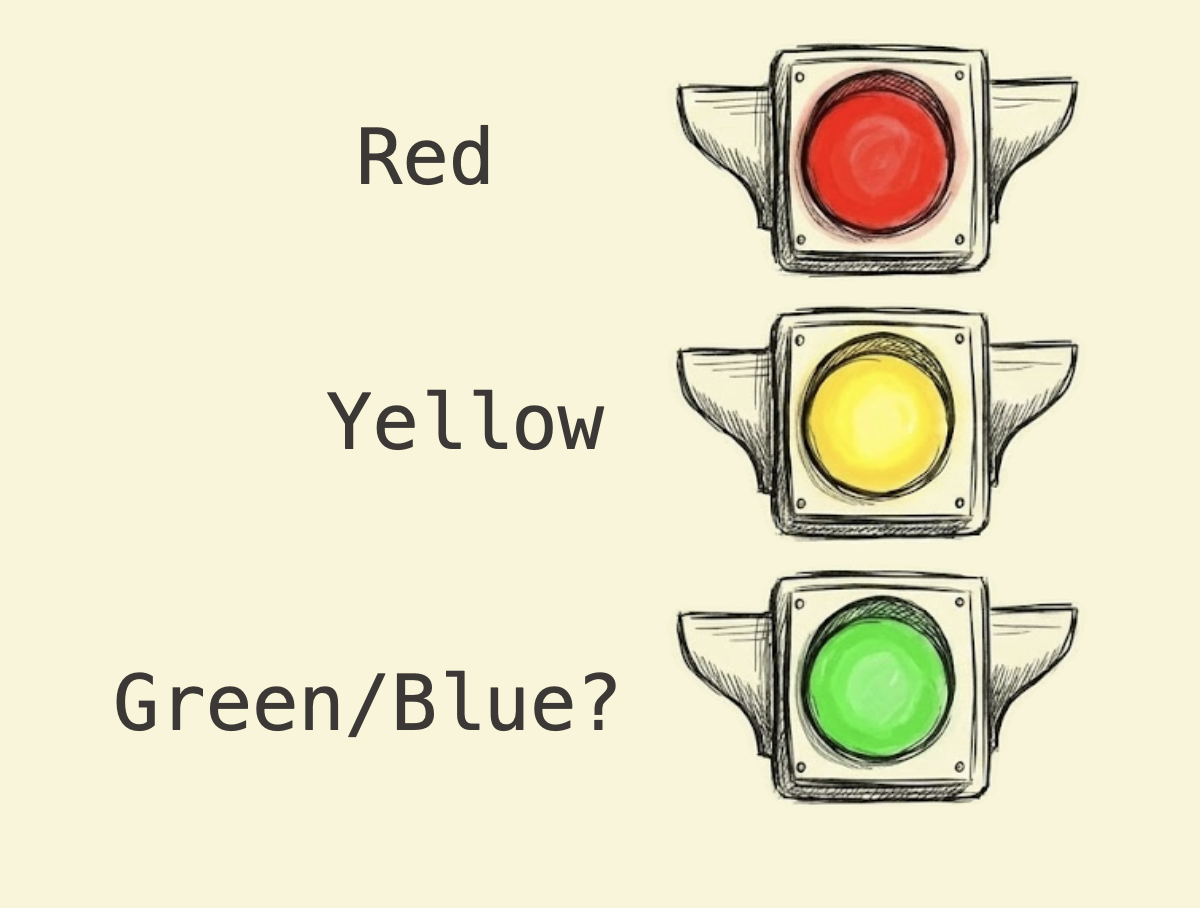

Shift your attention to color. We perceive the continuous variation of light as discrete categories (red, green, blue), but this categorization is not universal. Different languages carve up the color spectrum differently: a traffic light’s middle color is “green” in English but “blue” in Japanese, while English speakers see six colors in a rainbow compared to five in German and seven in Japanese.

All languages describe the same color space but categorize it differently. The boundaries we draw between colors are a choice, not a discovery. The same applies to generational differences: while cultural attitudes, technology exposure, and economic conditions do vary by birth cohort, this variation is continuous. The discrete labels we overlay are a choice about how to slice the continuum, not a discovery of where nature has already sliced it.

The Ship of Theseus in Your Body

Let’s push deeper. Perhaps generational boundaries are arbitrary, but surely physical objects have clear boundaries. A ship is a ship. Your body is your body. Right?

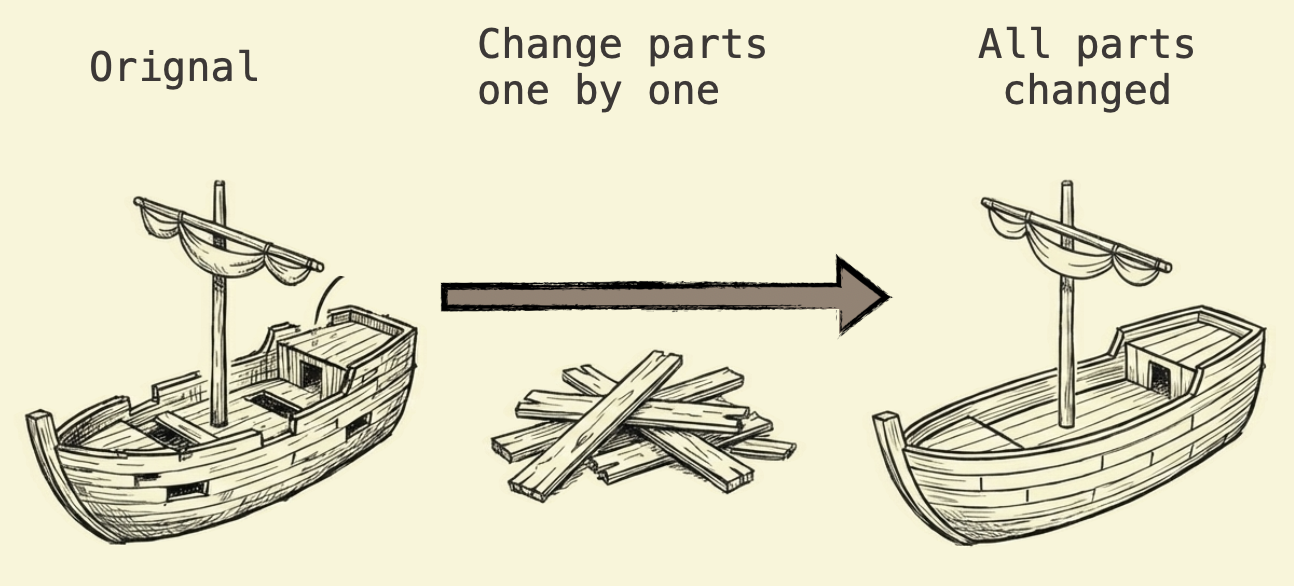

The Ship of Theseus paradox asks what happens when every plank of a wooden ship gets replaced over time. After thirty years at sea, not a single original board remains. Is it still the same ship?

If you gathered all the discarded planks and reassembled them, which ship is the real Theseus?

Your body presents the same puzzle. Nearly every atom in your body gets replaced on a rolling basis. Your skin cells regenerate every few weeks. Your red blood cells last about four months. Even your skeleton completely rebuilds itself every decade.

The “you” that exists today shares almost no physical matter with the “you” of ten years ago. Yet you maintain continuity of identity.

Where is the boundary of “you”? It’s not spatial, because your atoms disperse and are replaced. It’s not temporal, because you persist despite complete material turnover.

The boundary is conceptual. It’s imposed by the observer who needs a stable node labeled “person” to construct social networks, legal systems, and narratives of selfhood.

Why Boundaries Matter

This philosophical excursion has direct implications for how we model systems. Systems consist of parts, and parts require boundaries. But if the phenomena we’re studying are continuous, where do we draw those boundaries?

Traditional machine learning inherits this problem. Classification algorithms learn decision boundaries that divide feature space into regions, with each region getting a sharp label: you’re either Class A or Class B, with no middle ground. This works when categories are truly discrete (an email is spam or not spam), but it fails when the underlying phenomenon is continuous. Political ideology, disease severity, aesthetic preference all resist binary classification.

The Way Forward

What if we could work with the gradation directly instead of forcing it into boxes? What if meaning didn’t require boundaries? This is the insight that representation learning provides: by mapping concepts into continuous vector spaces, we preserve the relational structure that gives things meaning without imposing artificial divisions.

The next section explores where this insight comes from, tracing it back to structural linguistics and the radical claim that meaning emerges from difference rather than essence. Then we’ll see how modern machine learning operationalizes this philosophical stance, turning it from theory into working technology.

Think of three categories that feel natural to you (political party, music genre, personality type). For each one, try to identify specific cases that fall on the boundary. Why is it hard to categorize them? What does this reveal about the nature of the category itself?