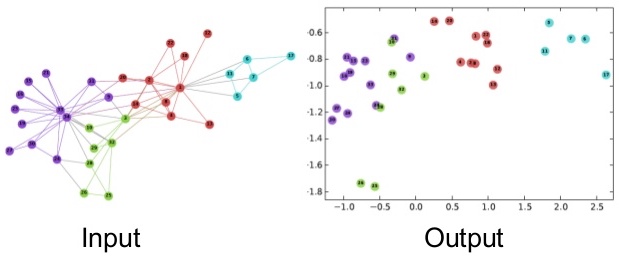

# Load the karate club network

g = igraph.Graph.Famous("Zachary")

A = g.get_adjacency_sparse()

# Get community labels (Mr. Hi = 0, Officer = 1)

labels = np.array([0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1])

g.vs["label"] = labels

# Visualize the network

palette = sns.color_palette().as_hex()

igraph.plot(g, vertex_color=[palette[label] for label in labels], bbox=(300, 300))Graph Embeddings

This module introduces graph embeddings that transform networks into continuous vector spaces.

You’ll learn:

- What network embedding means and how to compress graphs into low-dimensional representations.

- How to use spectral methods (adjacency, modularity, Laplacian) for finding optimal embeddings through eigendecomposition.

- The power of neural embeddings with word2vec, DeepWalk, and node2vec for learning from random walks.

- Practical techniques for clustering, visualization, and downstream machine learning tasks on graph data.

What is Network Embedding?

Networks are high-dimensional discrete structures that resist traditional machine learning algorithms designed for continuous data. Network embedding transforms graphs into low-dimensional continuous spaces where each node becomes a point in \mathbb{R}^d (typically d \ll N) while preserving important structural properties.

The goal is simple but powerful. Map nodes to vectors such that similar nodes have similar embeddings.

What does “similar” mean? It can mean many things: connected by edges, sharing neighbors, playing similar structural roles, or belonging to the same community.

Spectral Embeddings

Let’s talk about spectral methods. They use eigendecomposition to find low-dimensional representations. We explore three approaches: adjacency-based, modularity-based, and Laplacian-based.

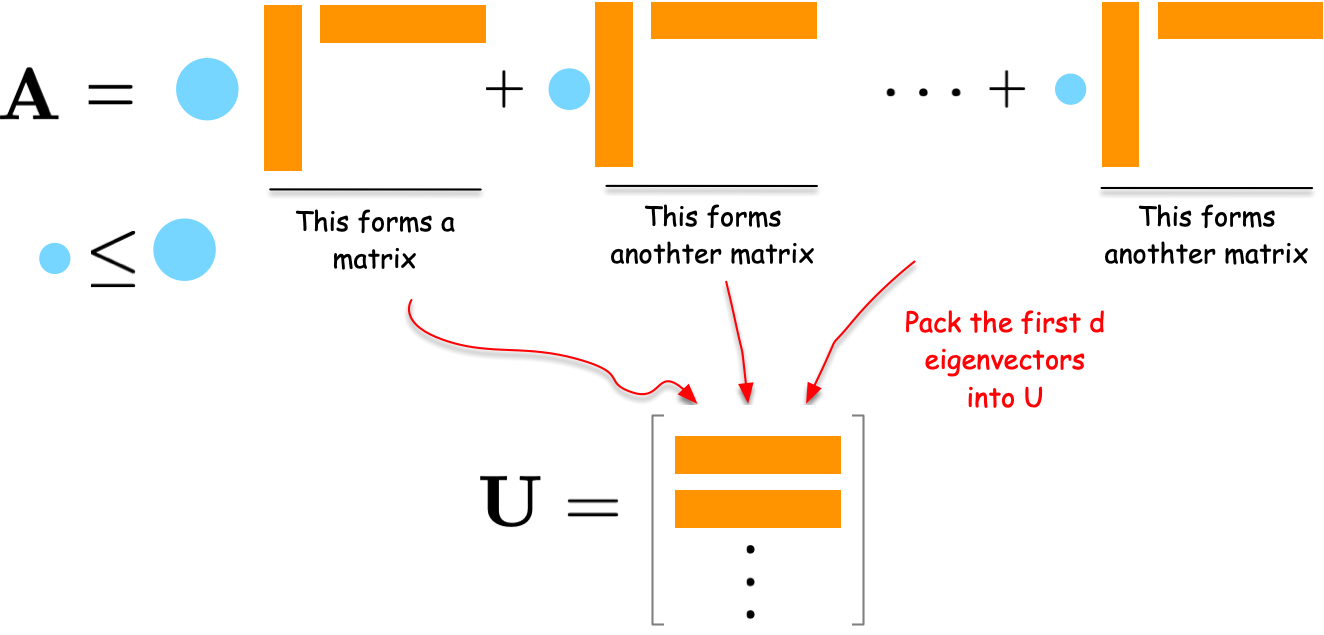

Compressing Networks

Suppose we have an adjacency matrix {\bf A} of size N \times N. We want to compress it into a matrix {\bf U} of size N \times d where d \ll N.

Good embeddings should reconstruct the original network well:

\min_{{\bf U}} J({\bf U}), \quad J({\bf U}) = \| {\bf A} - {\bf U}{\bf U}^\top \|_F^2

where \|\cdot\|_F is the Frobenius norm (sum of squared elements). The outer product {\bf U}{\bf U}^\top reconstructs the adjacency matrix from embeddings. Minimizing the difference between {\bf A} and this reconstruction yields the best low-dimensional representation.

Spectral Decomposition Solution

How do we solve this optimization problem? Consider the eigendecomposition of {\bf A}:

{\bf A} = \sum_{i=1}^N \lambda_i {\bf u}_i {\bf u}_i^\top

Each term \lambda_i {\bf u}_i {\bf u}_i^\top is a rank-one matrix capturing part of the network structure. Eigenvalues \lambda_i indicate importance.

To compress the network, select the d eigenvectors with largest eigenvalues and form embedding matrix {\bf U} = [{\bf u}_1, {\bf u}_2, \ldots, {\bf u}_d]. This is provably optimal for minimizing reconstruction error.

Modularity Embedding

What if we want to emphasize community structure? Instead of the adjacency matrix, we can embed the modularity matrix:

Q_{ij} = \frac{1}{2m}A_{ij} - \frac{k_i k_j}{4m^2}

where k_i is node degree and m is the number of edges. The modularity matrix emphasizes connections beyond what random chance predicts.

Its eigenvectors naturally separate communities. A simple community detection algorithm: group nodes by the sign of the second eigenvector (Newman 2006).

Laplacian Eigenmap

Laplacian Eigenmap (Belkin and Niyogi 2003) positions connected nodes close together. The optimization problem is:

\min_{{\bf U}} J_{LE}({\bf U}), \quad J_{LE}({\bf U}) = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i,j} A_{ij} \| {\bf u}_i - {\bf u}_j \|^2

Through algebraic manipulation, this becomes:

J_{LE}({\bf U}) = \text{Tr}({\bf U}^\top {\bf L} {\bf U})

where {\bf L} = {\bf D} - {\bf A} is the graph Laplacian and \text{Tr} denotes the trace. The derivation proceeds as follows:

\begin{aligned} J_{LE} &= \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i,j} A_{ij} (\| {\bf u}_i \|^2 - 2 {\bf u}_i^\top {\bf u}_j + \| {\bf u}_j \|^2) \\ &= \sum_i k_i \| {\bf u}_i \|^2 - \sum_{i,j} A_{ij} {\bf u}_i^\top {\bf u}_j \\ &= \text{Tr}({\bf U}^\top {\bf D} {\bf U}) - \text{Tr}({\bf U}^\top {\bf A} {\bf U}) \\ &= \text{Tr}({\bf U}^\top {\bf L} {\bf U}) \end{aligned}

The solution is the d eigenvectors corresponding to the smallest eigenvalues of {\bf L} (excluding the trivial zero eigenvalue). The smallest eigenvalue is always zero with eigenvector of all ones. In practice, compute d+1 smallest eigenvectors and discard the first.

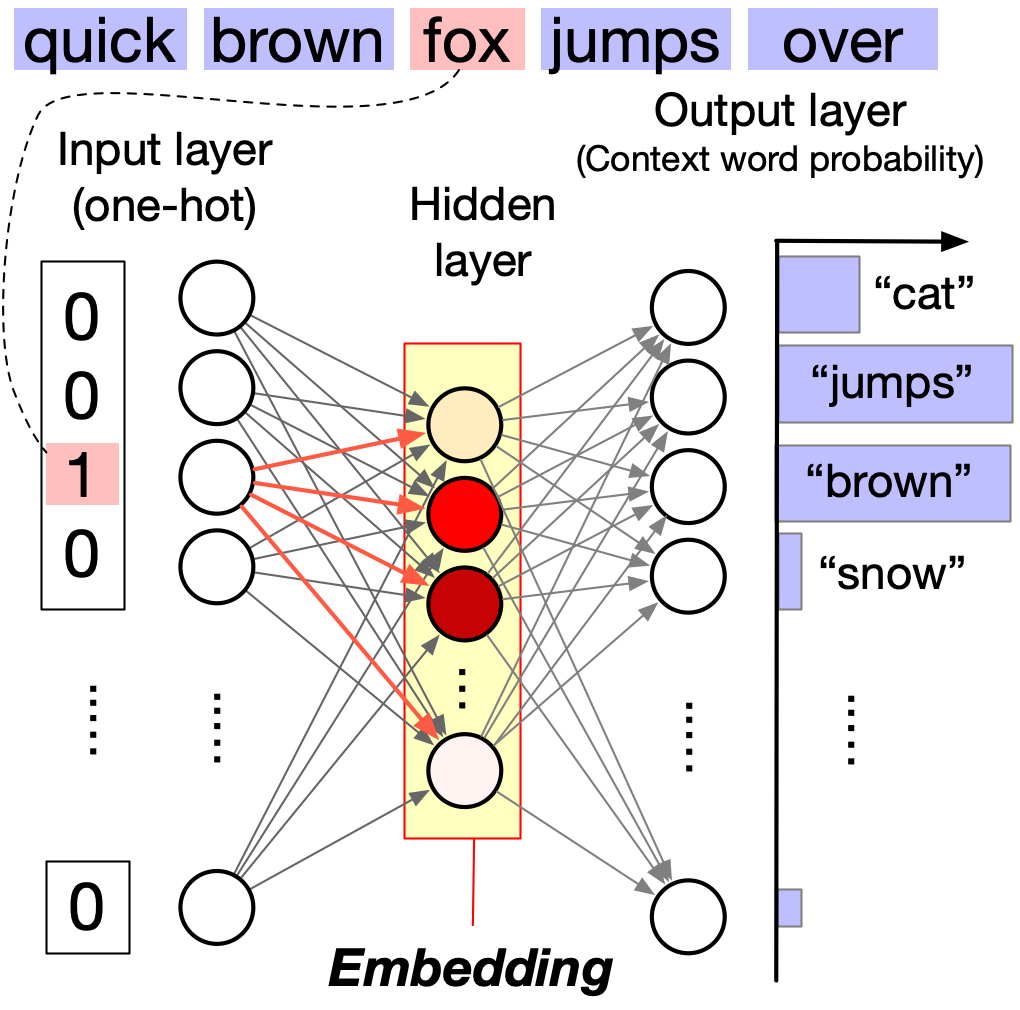

Neural Embeddings with word2vec

Spectral methods are elegant but computationally expensive for large graphs. What’s the alternative?

Neural methods learn embeddings using neural networks trained on data. Before applying these to graphs, we introduce word2vec, which forms the foundation for many graph embedding techniques.

How word2vec Works

word2vec (Mikolov et al. 2013) learns word meanings from context, following the principle: “You shall know a word by the company it keeps” (church1988word?). This phrase comes from Aesop’s fable The Ass and his Purchaser. A man brings an ass to his farm on trial. The ass immediately joins the laziest, greediest ass in the herd. The man returns it, knowing its character by the company it chose.

The core idea is simple. Given a target word, predict surrounding context words within a fixed window. For example, in “The quick brown fox jumps over a lazy dog,” the context of fox (window size 2) includes quick, brown, jumps, over.

Words appearing in similar contexts get similar embeddings. Both fox and dog appear with “quick,” “brown,” and action verbs, so they have similar embeddings. But student appears with “studies” and “library,” giving it a distant embedding.

The network architecture has three layers. The input layer uses one-hot encoding of the target word. The hidden layer holds the learned word embedding (low-dimensional). The output layer produces a probability distribution over context words using softmax.

The hidden layer activations become dense, low-dimensional vectors capturing semantic relationships. For a visual walkthrough, see The Illustrated Word2vec by Jay Alammar.

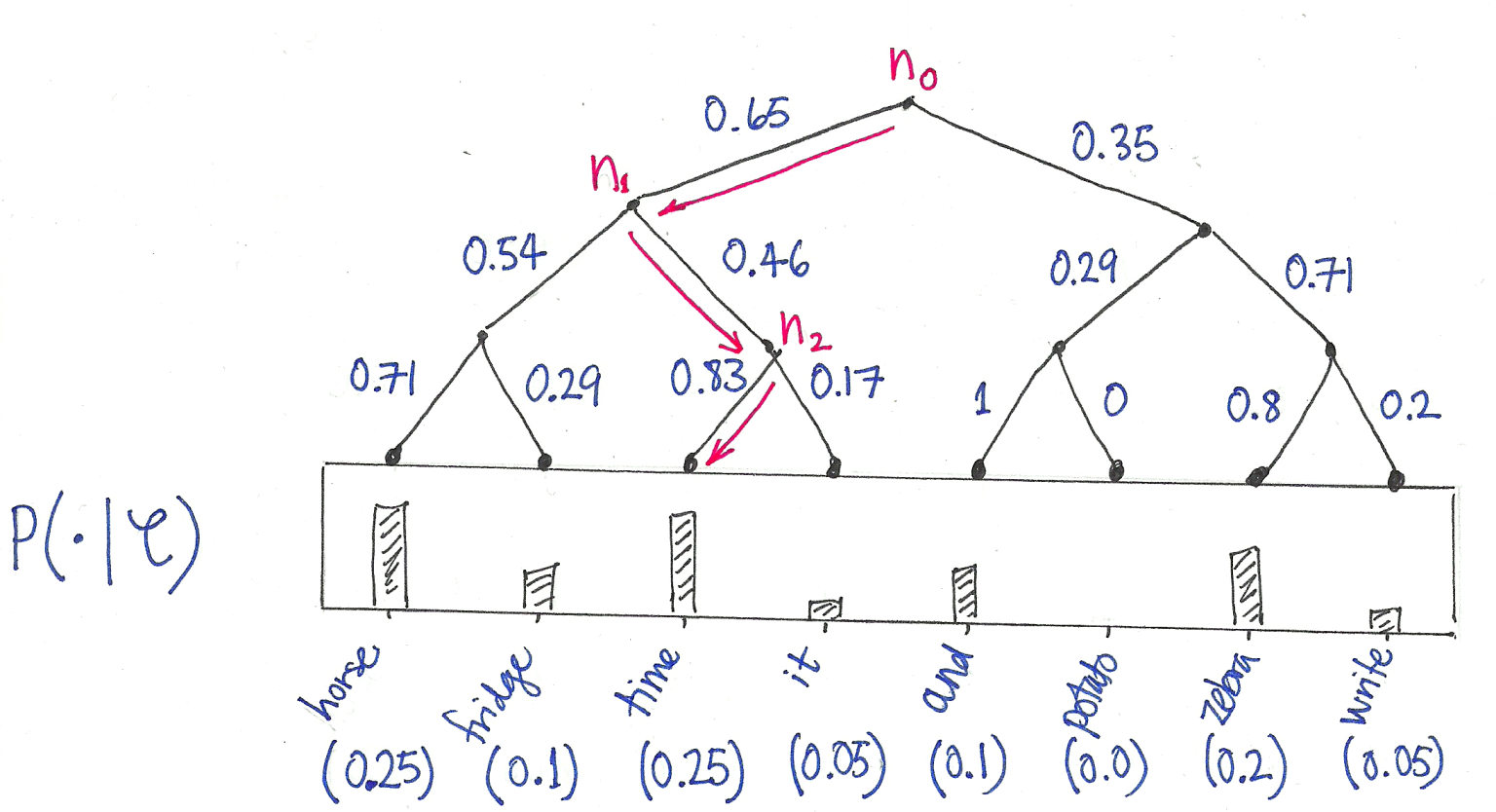

Efficient Training

Why don’t we use this architecture directly? Computing the full softmax over vocabulary is expensive:

P(w_c | w_t) = \frac{\exp({\bf v}_{w_c} \cdot {\bf v}_{w_t})}{\sum_{w \in V} \exp({\bf v}_w \cdot {\bf v}_{w_t})}

The denominator sums over all words (100,000+ terms), making training slow.

Two solutions exist:

Hierarchical Softmax: Organizes vocabulary as a binary tree. Computing probability becomes traversing root-to-leaf paths, reducing complexity from \mathcal{O}(|V|) to \mathcal{O}(\log |V|).

Negative Sampling: Instead of normalizing over all words, sample a few “negative” (non-context) words and contrast them with true context words. This approximates the full softmax efficiently with 5-20 negative samples.

word2vec’s Power

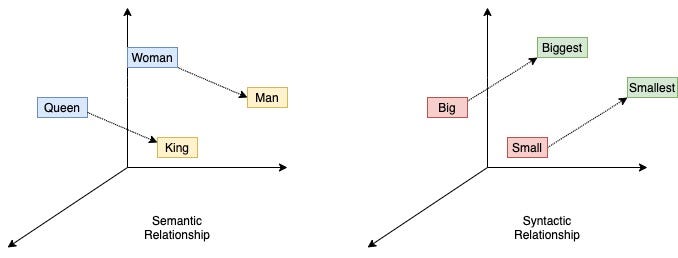

What makes word2vec special? word2vec embeddings capture semantic relationships through simple linear algebra:

Famous examples include analogies: man is to woman as king is to queen. Relationships like countries and capitals form parallel vectors in the embedding space.

Graph Embedding with word2vec

How can we apply word2vec to graphs? The challenge is that word2vec expects sequences, while graphs are unordered.

The solution: random walks transform graphs into sequences of nodes. Treat walks as sentences and nodes as words. Random walks create “sentences” from graphs where each walk is a sequence of nodes, just like a sentence is a sequence of words.

DeepWalk

DeepWalk (Perozzi, Al-Rfou, and Skiena 2014) pioneered applying word2vec to graphs:

- Sample multiple random walks from the graph

- Treat walks as sentences and feed them to word2vec

DeepWalk uses skip-gram with hierarchical softmax for efficient training. Nodes appearing in similar walk contexts get similar embeddings.

node2vec

What if we want more control over the random walks? node2vec (Grover and Leskovec 2016) extends DeepWalk with biased random walks controlled by parameters p and q:

P(v_{t+1} = x | v_t = v, v_{t-1} = t) \propto \begin{cases} \frac{1}{p} & \text{if } d(t,x) = 0 \text{ (return to previous)} \\ 1 & \text{if } d(t,x) = 1 \text{ (close neighbor)} \\ \frac{1}{q} & \text{if } d(t,x) = 2 \text{ (explore further)} \end{cases}

where d(t,x) is the shortest path from previous node t to candidate x. Low p creates return bias (local revisiting). Low q creates outward bias (exploration, DFS-like). High q creates inward bias (stay local, BFS-like).

These parameters enable two exploration strategies. BFS-like walks (low q) explore immediate neighborhoods and capture community structure. DFS-like walks (high q) explore deep paths and capture structural roles.

Note that node2vec uses negative sampling instead of hierarchical softmax, affecting embedding characteristics (Kojaku et al. 2021; Dyer 2014).

LINE

LINE (Tang et al. 2015) is equivalent to node2vec with p=1, q=1, and window size 1. It directly optimizes graph structure preservation.

Neural methods seem less transparent than spectral methods, but recent work establishes equivalences under specific conditions (Qiu et al. 2018; kojaku2024network?). Surprisingly, DeepWalk, node2vec, and LINE are provably optimal for stochastic block models (kojaku2024network?).

Hands-On: Implementing Embeddings

Let’s implement these methods on the Karate Club network.

Data Preparation

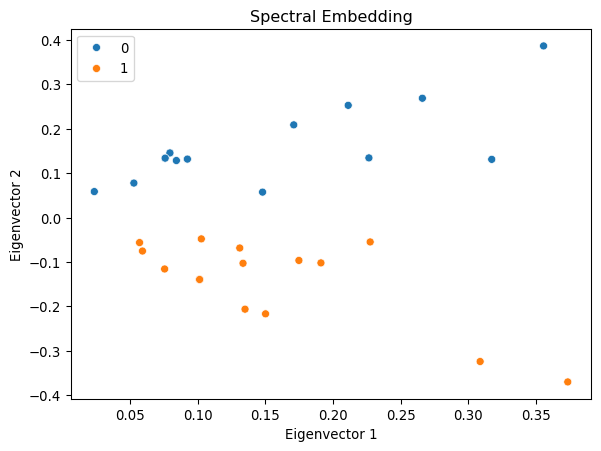

Spectral Embedding Example

# Compute the spectral decomposition

A_dense = A.toarray()

eigvals, eigvecs = np.linalg.eig(A_dense)

# Find the top d eigenvectors

d = 2

sorted_indices = np.argsort(eigvals)[::-1][:d]

eigvecs_top = eigvecs[:, sorted_indices]Show visualization code

# Plot the results

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(7, 5))

sns.scatterplot(x=eigvecs_top[:, 0], y=eigvecs_top[:, 1], hue=labels, ax=ax)

ax.set_title('Spectral Embedding')

ax.set_xlabel('Eigenvector 1')

ax.set_ylabel('Eigenvector 2')

plt.show()/Users/skojaku-admin/miniforge3/envs/advnetsci/lib/python3.11/site-packages/matplotlib/cbook.py:1709: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part

return math.isfinite(val)

/Users/skojaku-admin/miniforge3/envs/advnetsci/lib/python3.11/site-packages/matplotlib/cbook.py:1709: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part

return math.isfinite(val)

/Users/skojaku-admin/miniforge3/envs/advnetsci/lib/python3.11/site-packages/pandas/core/dtypes/astype.py:133: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part

return arr.astype(dtype, copy=True)

/Users/skojaku-admin/miniforge3/envs/advnetsci/lib/python3.11/site-packages/pandas/core/dtypes/astype.py:133: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part

return arr.astype(dtype, copy=True)

The first eigenvector corresponds to eigencentrality. The second eigenvector captures community structure, clearly separating the two groups.

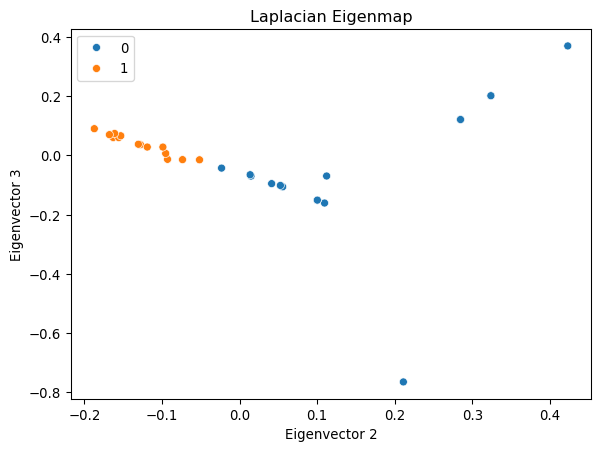

Laplacian Eigenmap Example

# Compute the Laplacian

D = np.diag(np.sum(A_dense, axis=1))

L = D - A_dense

eigvals_L, eigvecs_L = np.linalg.eig(L)

# Sort and select eigenvalues (exclude first)

sorted_indices_L = np.argsort(eigvals_L)[1:d+1]

eigvecs_L_top = eigvecs_L[:, sorted_indices_L]Show visualization code

# Plot the results

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(7, 5))

sns.scatterplot(x=eigvecs_L_top[:, 0], y=eigvecs_L_top[:, 1], hue=labels, ax=ax)

ax.set_title('Laplacian Eigenmap')

ax.set_xlabel('Eigenvector 2')

ax.set_ylabel('Eigenvector 3')

plt.show()

DeepWalk Example

Show random walk implementation

def random_walk(net, start_node, walk_length):

"""Generate a random walk starting from start_node."""

walk = [start_node]

while len(walk) < walk_length:

cur = walk[-1]

cur_nbrs = list(net[cur].indices)

if len(cur_nbrs) > 0:

walk.append(np.random.choice(cur_nbrs))

else:

break

return walk

# Generate random walks

n_nodes = g.vcount()

n_walkers_per_node = 10

walk_length = 50

walks = []

for i in range(n_nodes):

for _ in range(n_walkers_per_node):

walks.append(random_walk(A, i, walk_length))

print(f"Generated {len(walks)} random walks")

print(f"Example walk: {walks[0][:10]}...")Generated 340 random walks

Example walk: [0, 13, 2, 0, 3, 13, 3, 12, 3, 12]...# Train word2vec on the walks

model = Word2Vec(

walks,

vector_size=32,

window=3,

min_count=1,

sg=1, # Skip-gram

hs=1, # Hierarchical softmax

workers=1,

)

# Extract embeddings

embedding = np.array([model.wv[i] for i in range(n_nodes)])

print(f"Embedding matrix shape: {embedding.shape}")Embedding matrix shape: (34, 32)/Users/skojaku-admin/miniforge3/envs/advnetsci/lib/python3.11/site-packages/umap/umap_.py:1952: UserWarning: n_jobs value 1 overridden to 1 by setting random_state. Use no seed for parallelism.

warn(

OMP: Info #276: omp_set_nested routine deprecated, please use omp_set_max_active_levels instead.Nodes from the same community cluster together, showing that DeepWalk captures community structure.

Clustering with K-means

Show clustering implementation

def find_optimal_clusters(embedding, n_clusters_range=(2, 10)):

"""Find optimal number of clusters using silhouette score."""

silhouette_scores = []

for n_clusters in range(*n_clusters_range):

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=n_clusters, random_state=42)

cluster_labels = kmeans.fit_predict(embedding)

score = silhouette_score(embedding, cluster_labels)

silhouette_scores.append((n_clusters, score))

print(f"k={n_clusters}: silhouette score = {score:.3f}")

optimal_k = max(silhouette_scores, key=lambda x: x[1])[0]

print(f"\nOptimal number of clusters: {optimal_k}")

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=optimal_k, random_state=42)

return kmeans.fit_predict(embedding)

# Find clusters

cluster_labels = find_optimal_clusters(embedding)k=2: silhouette score = 0.444

k=3: silhouette score = 0.466

k=4: silhouette score = 0.518

k=5: silhouette score = 0.453

k=6: silhouette score = 0.359

k=7: silhouette score = 0.397

k=8: silhouette score = 0.359

k=9: silhouette score = 0.350

Optimal number of clusters: 4Show clustering visualization

# Visualize clustering

cmap = sns.color_palette().as_hex()

igraph.plot(

g,

vertex_color=[cmap[label] for label in cluster_labels],

bbox=(500, 500),

vertex_size=20

)K-means successfully identifies communities using only learned embeddings, demonstrating that DeepWalk captures meaningful structural properties.

Comparing Approaches

Which method should you use? We have explored multiple embedding methods, each with distinct trade-offs:

| Method | Approach | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral (Adjacency) | Eigendecomposition | Principled, captures centrality | Expensive, requires full graph |

| Laplacian Eigenmap | Minimize edge distances | Preserves local structure | Sensitive to disconnected components |

| DeepWalk | Random walks + word2vec | Scalable, flexible | Random initialization sensitive |

| node2vec | Biased random walks | Controls exploration | More hyperparameters |

Spectral methods offer mathematical guarantees but scale poorly. Neural methods scale to large graphs and generalize to unseen nodes but require careful hyperparameter tuning.

Are these methods fundamentally different? Recent work shows these methods are more connected than they appear. Under specific conditions, neural embeddings provably approximate spectral embeddings (Qiu et al. 2018; kojaku2024network?). This bridges the gap between elegant theory and practical scalability.

Key Takeaways

Graph embeddings transform discrete networks into continuous vector spaces, enabling standard machine learning algorithms. Spectral methods use eigendecomposition to find optimal low-dimensional representations. Neural methods learn embeddings by treating random walks as training data for word2vec.

These embeddings power downstream tasks: node classification, link prediction, community detection, and visualization. They bridge the gap between graph theory and deep learning, showing that geometric intuitions about similarity and distance extend naturally to network data.

What have we learned in this module? We journeyed from pixels to nodes, extending convolution beyond regular grids. We explored spectral and spatial perspectives on graph neural networks. We learned how embeddings compress networks into vectors while preserving structure.

The principles transcend specific architectures. Locality matters. Parameter sharing generalizes. Hierarchical features extract increasingly abstract patterns. These insights apply wherever relationships exist, from molecules to social networks to knowledge graphs.