Part 2: Meaning as Difference

This module introduces the structuralist view of meaning.

You’ll learn:

- What Saussure’s theory of signs reveals about how language creates meaning through difference, not essence.

- How Apoha (Buddhist logic of negation) independently discovered that concepts are defined by exclusion.

- Why Jakobson’s binary features turn phonemes into coordinates in a geometric space.

- How metaphor and metonymy represent two fundamental modes of cognitive connection.

- The practical connection between structuralist philosophy and machine learning algorithms like word2vec.

The Arbitrary Nature of Signs

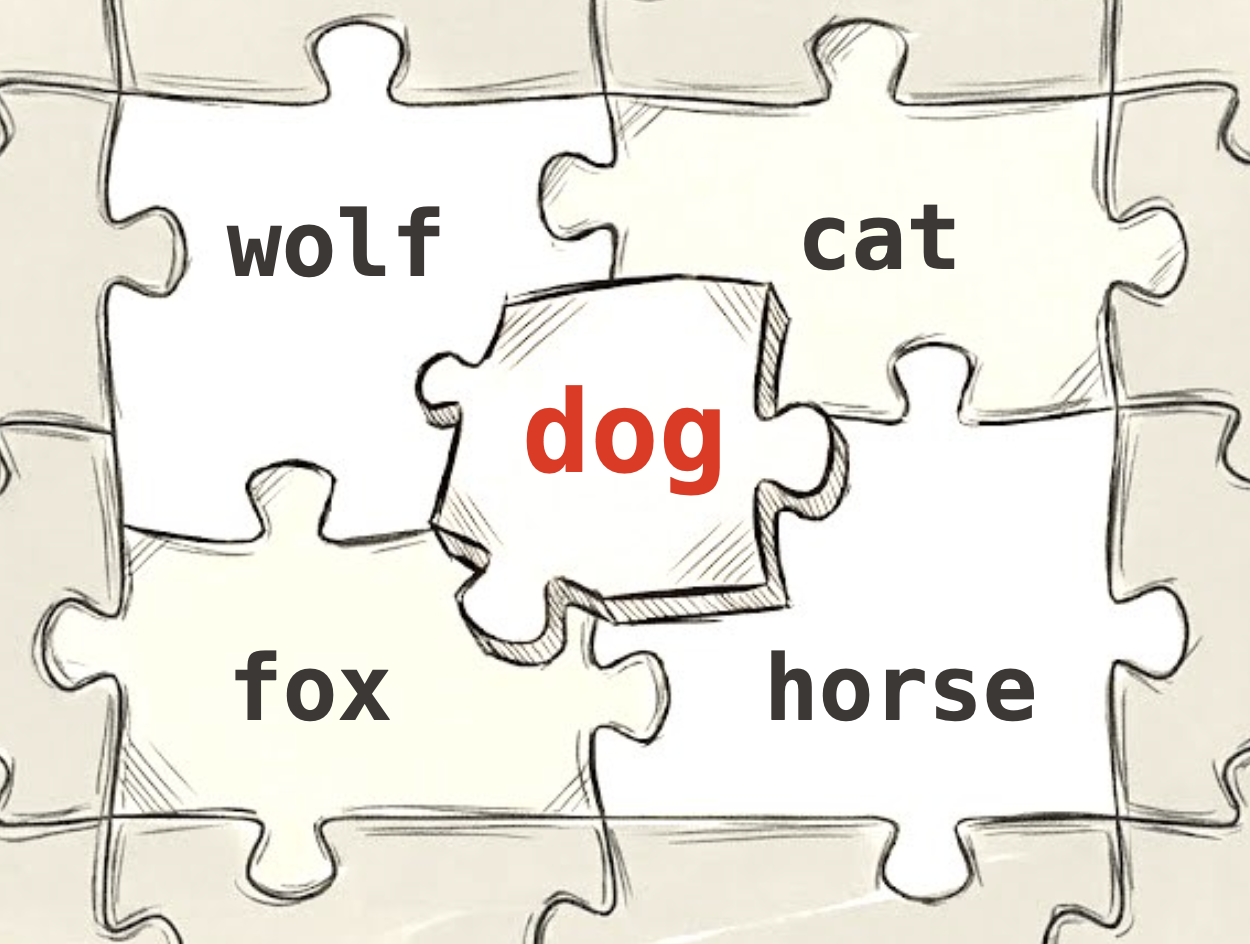

Let’s start with a simple observation that changes everything. What makes the English word “dog” mean what it means? You might answer that it refers to a four-legged canine animal, but why those particular sounds and not “chien” (French), “perro” (Spanish), or “犬” (Japanese)? The connection between the sound pattern and the concept is arbitrary.

Ferdinand de Saussure, the founder of modern linguistics, called this the arbitrariness of the sign. A sign has two parts: the signifier (the sound or written form) and the signified (the concept), and the relationship between them is not natural or inevitable but a social convention. Saussure went further and argued that the signified (the concept itself) is also arbitrary. We think “dog” refers to a pre-existing natural category, but nature doesn’t draw boundaries between dogs, wolves, and foxes. We do.

Different languages slice the animal kingdom differently. Some languages have multiple words for what English calls “rice” (depending on whether it’s cooked or raw). English distinguishes “river” from “stream” where other languages use one word. The concepts themselves are products of how a language chooses to divide conceptual space.

What does this reveal? The meaning of “dog” isn’t determined by what dogs are. It’s determined by what dogs are not. “Dog” means “dog” because it occupies a specific position in a network of differences: not “cat”, not “wolf”, not “fox”, not “log”, not “fog”.

Apoha: Buddhist Logic of Negation

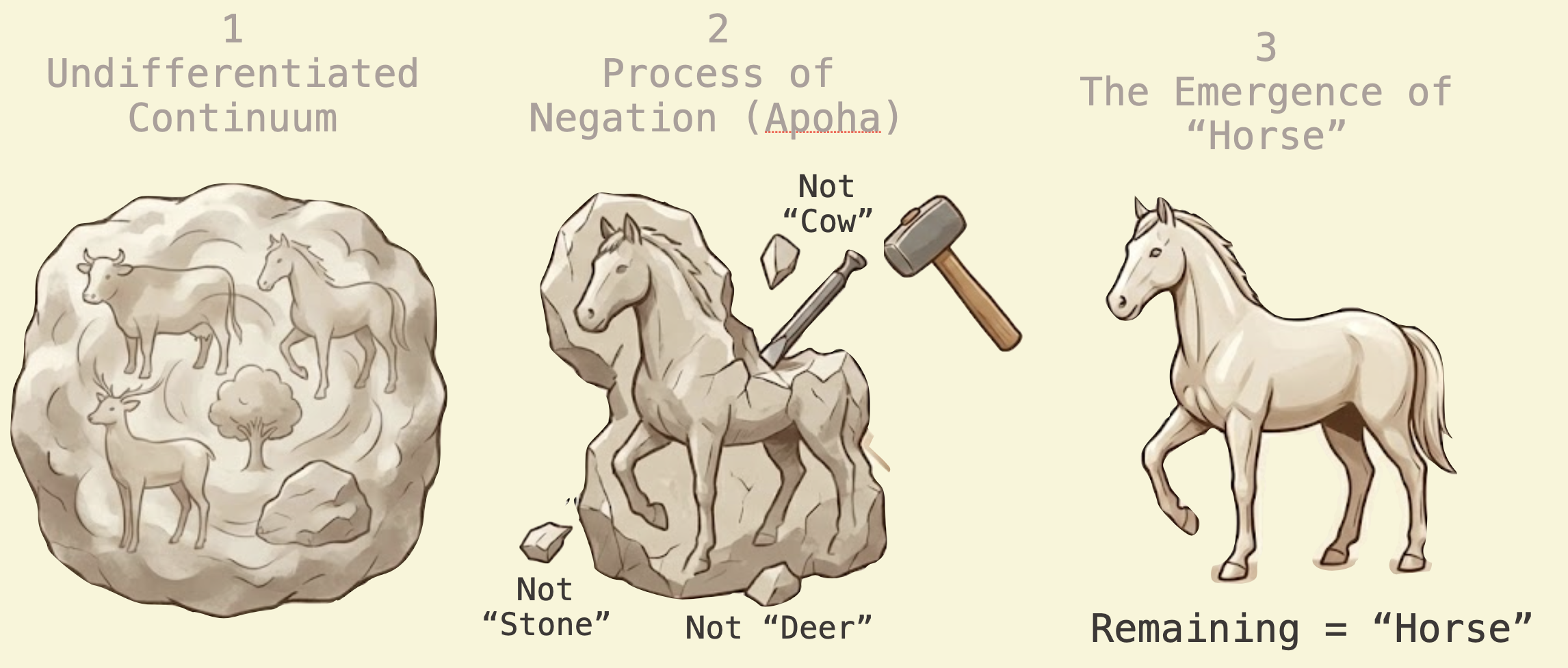

This idea that concepts are defined through negation has deep roots. Buddhist philosophers in ancient India developed a theory called Apoha (literally “exclusion”) around the 5th century CE. They argued that we cannot understand what a thing is, only what it is not.

When you see a horse, you don’t directly grasp “horseness”. Instead, you implicitly exclude everything that is not-horse: not-cow, not-stone, not-water, not-tree. The concept of “horse” is nothing more than the region of conceptual space that remains after all these exclusions. It’s a purely negative definition.

Dignāga and Dharmakīrti, the primary developers of Apoha theory, influenced both Indian and Tibetan Buddhist philosophy. Their ideas parallel Saussure’s insights developed independently 1400 years later.

Why does this matter? Categories are not containers holding essences but regions in a space of possibilities carved out by contrast. You don’t need to know what something is, only what it is not. The meaning is in the boundaries, not the interior.

Jakobson’s Binary Oppositions

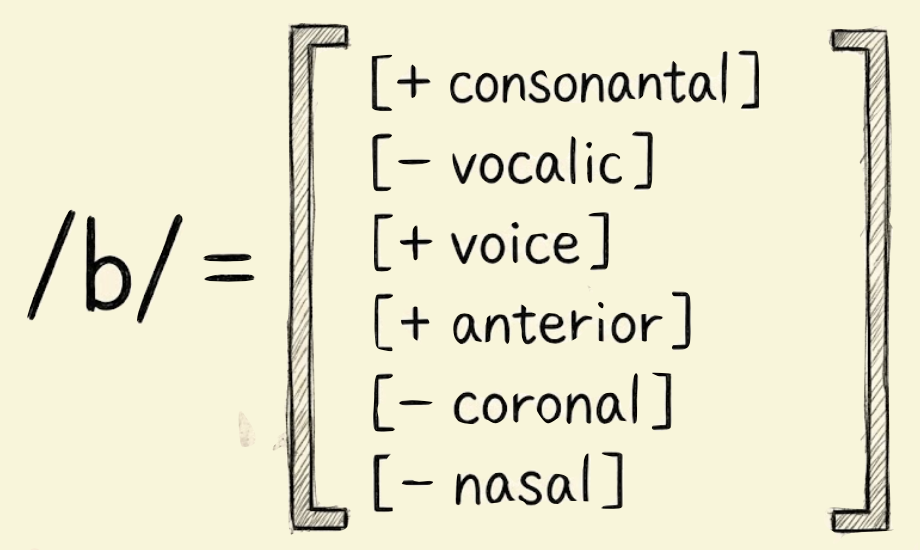

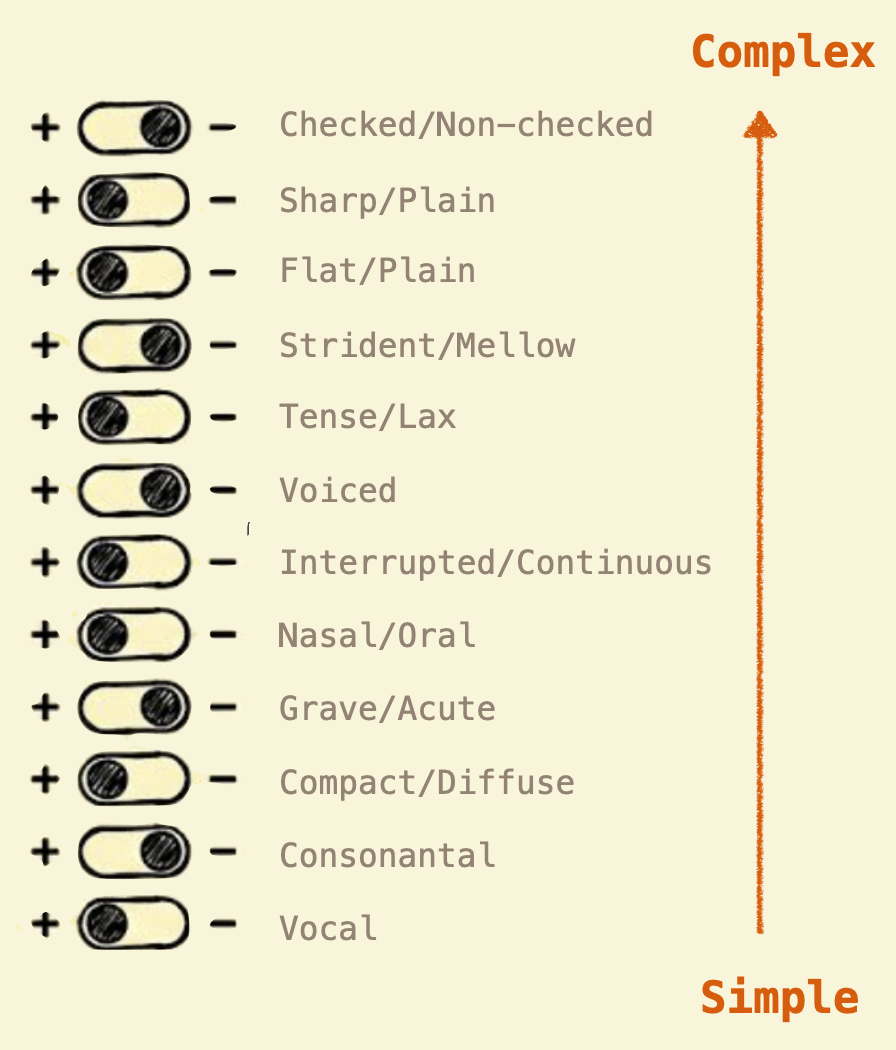

Roman Jakobson, a 20th-century linguist, took the structuralist insight and formalized it. He studied phonemes (the basic sound units of language) and showed they could be decomposed into binary features.

Consider the difference between “p” and “b”. They’re produced almost identically: both are bilabial stops (you close your lips and release air). The only difference is voicing. Your vocal cords vibrate for “b” but not for “p”.

We can represent this as:

- “p”: [+bilabial, +stop, -voiced]

- “b”: [+bilabial, +stop, +voiced]

Jakobson showed that all phonemes in all languages could be analyzed as bundles of such binary oppositions: voiced/voiceless, nasal/oral, fricative/stop, and so on. A phoneme isn’t a sound. It’s a position in a multidimensional space of contrasts.

What does this mean practically? Each phoneme is represented not by a symbol but by a coordinate in feature space. Two phonemes are similar if their feature vectors are close. The entire phonological system of a language becomes a geometry problem.

Why Babies Say “Mama” and “Papa” Everywhere

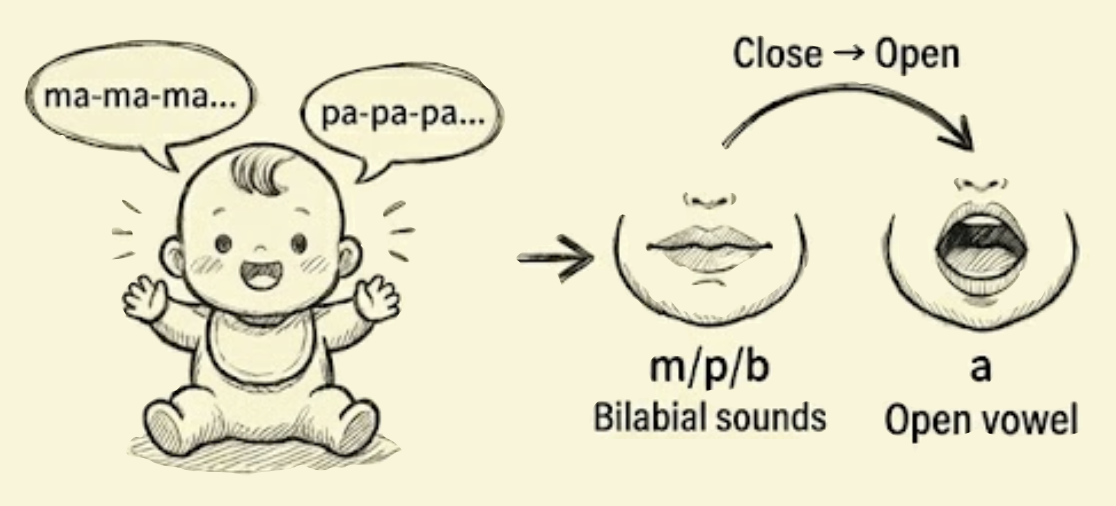

Let’s make this concrete with one of the most striking examples of phonological universals. Consider how remarkably similar the words for “mother” and “father” are across completely unrelated languages: English “Mama”/“Papa”, Mandarin “妈妈 (Māma)”/“爸爸 (Bàba)”, Swahili “Mama”, Hebrew “Ima”, French “Papa”, Italian “Babbo”, Spanish “Mamá”, Turkish “Baba”. Why do languages separated by continents and millennia converge on these particular sounds? The structuralist answer reveals something profound about how humans acquire language.

Babies don’t learn sounds in isolation. They learn contrasts. The first contrasts they master involve the most basic physiological oppositions their vocal apparatus can produce.

The first opposition is fully closed (m/p) versus fully open (a): the consonants “m” and “p” require complete closure of the lips while the vowel “a” requires maximum opening of the mouth, creating the most extreme articulatory contrast possible and the easiest distinction for infants to produce and perceive. The second opposition is nasal (m) versus oral (p): both involve closing the lips, but “m” lets air flow through the nose (nasal) while “p” blocks it completely and releases it as a burst (oral stop). This creates a minimal phonological system with maximum contrast, where “Mama” combines nasal closure with open vowel (repeated) and “Papa” combines oral closure with open vowel (repeated). The repetition itself is developmentally significant because reduplication is easier for infant motor systems than producing different syllables.

Jakobson argued that language acquisition follows an implicational hierarchy. Children acquire contrasts in a universal order, from maximal to minimal distinctions. Complex sounds appear only after simpler foundations are established.

Distinctive Features as DNA

Jakobson’s insight was that you could decompose any phoneme into a bundle of binary features. Consider the phoneme /b/ (as in “baby”): it’s articulated [+labial] (at the lips), the vocal cords vibrate [+voiced], air doesn’t flow through the nose [-nasal], and airflow is stopped by [+stop] (complete closure, then release). The phoneme /b/ isn’t a primitive unit but a coordinate in feature space: [+labial, +voiced, -nasal, +stop, -continuant]. Change one feature and you get a different phoneme: flip [+voiced] to [-voiced] and you get /p/, or flip [+stop] to [-stop, +continuant] and you get /v/.

Jakobson identified roughly twelve distinctive features that are sufficient to describe the phonological systems of all human languages. These features aren’t arbitrary labels but correspond to physiological and acoustic properties of speech production and perception, meaning languages don’t choose their sounds randomly but select from a universal feature space defined by human biology.

What does this reveal? Phonological systems aren’t just collections of sounds but structured geometries, and languages can’t have random inventories of phonemes. If a language has a complex sound, it must also have the simpler contrasts that build up to it: if it distinguishes three levels of vowel height (high, mid, low), it must first distinguish high from non-high, and if it has voiced fricatives like /z/, it must have voiceless fricatives like /s/. The diversity of human languages doesn’t mean anything is possible but rather that there’s a universal space of phonological possibilities, and each language carves out a specific subset. The structure is in the oppositions, not the sounds themselves.

The Culinary Triangle

Claude Lévi-Strauss, the structural anthropologist, extended this approach beyond language to culture itself. He argued that human thought operates through binary oppositions: nature/culture, raw/cooked, male/female, sacred/profane. These aren’t universal truths. They’re structural patterns that organize how different societies make sense of experience.

His “culinary triangle” is a famous example. He analyzed how different cultures process food through two axes: the nature-culture axis (raw vs. transformed) and the means of transformation (cooking vs. rotting). This creates a conceptual space where different food preparation methods occupy specific positions.

Lévi-Strauss developed these ideas in The Raw and the Cooked (1964), the first volume of his four-volume Mythologiques series analyzing the structure of myths across cultures. Roasted meat sits between raw and cooked (less elaborated cooking), boiled meat is fully cooked (more elaborated), and fermented foods sit between raw and rotted (cultural transformation through natural processes). Each food type’s meaning comes from its position in this structural space, not from any intrinsic property. This is the structuralist thesis in full form: meaning is relational, not substantive, systems of meaning are systems of differences, and to understand anything you must map the space of contrasts.

Metaphor and Metonymy: Two Modes of Connection

Jakobson identified two fundamental ways that concepts connect: through similarity (metaphor) and through contiguity (metonymy). These aren’t just literary devices. They’re cognitive structures that organize how we think and how language operates.

Metaphor works by similarity: “Juliet is the sun” connects two unlike things through shared properties (brightness, warmth, centrality), letting us understand the abstract through the concrete and the unfamiliar through the familiar. Western philosophy and science tend toward metaphorical thinking, as classification systems, taxonomies, and abstraction hierarchies all rely on grouping similar things. Metonymy works by contiguity (spatial or conceptual adjacency): “The White House announced…” uses a location to refer to the president, and “Hollywood is obsessed with franchises” uses a place to refer to the film industry. Metonymy captures association, co-occurrence, and context, and Eastern philosophy often emphasizes metonymic thinking by understanding things through their relationships and contexts rather than their essential properties.

Jakobson argued that aphasia patients show selective impairment of either metaphoric (similarity-based) or metonymic (contiguity-based) operations, suggesting these are fundamental cognitive mechanisms.

Why does this distinction matter for machine learning? Different algorithms capture different types of relationships. Classification algorithms and clustering methods are metaphorical (they group by similarity). But sequence models, language models, and graph neural networks are metonymic (they learn from co-occurrence and context). Understanding which type of relationship you’re trying to capture shapes which tools you should use.

Discover Your Cognitive Style

Let’s test which mode of thinking comes more naturally to you. Research suggests that cultural background, language, and experience shape whether we lean toward metaphorical (similarity-based) or metonymic (context-based) reasoning. Take this quick diagnostic.

For each scenario below, choose the interpretation (A or B) that feels most natural to you. There are no right or wrong answers. This reveals something about how your mind organizes meaning.

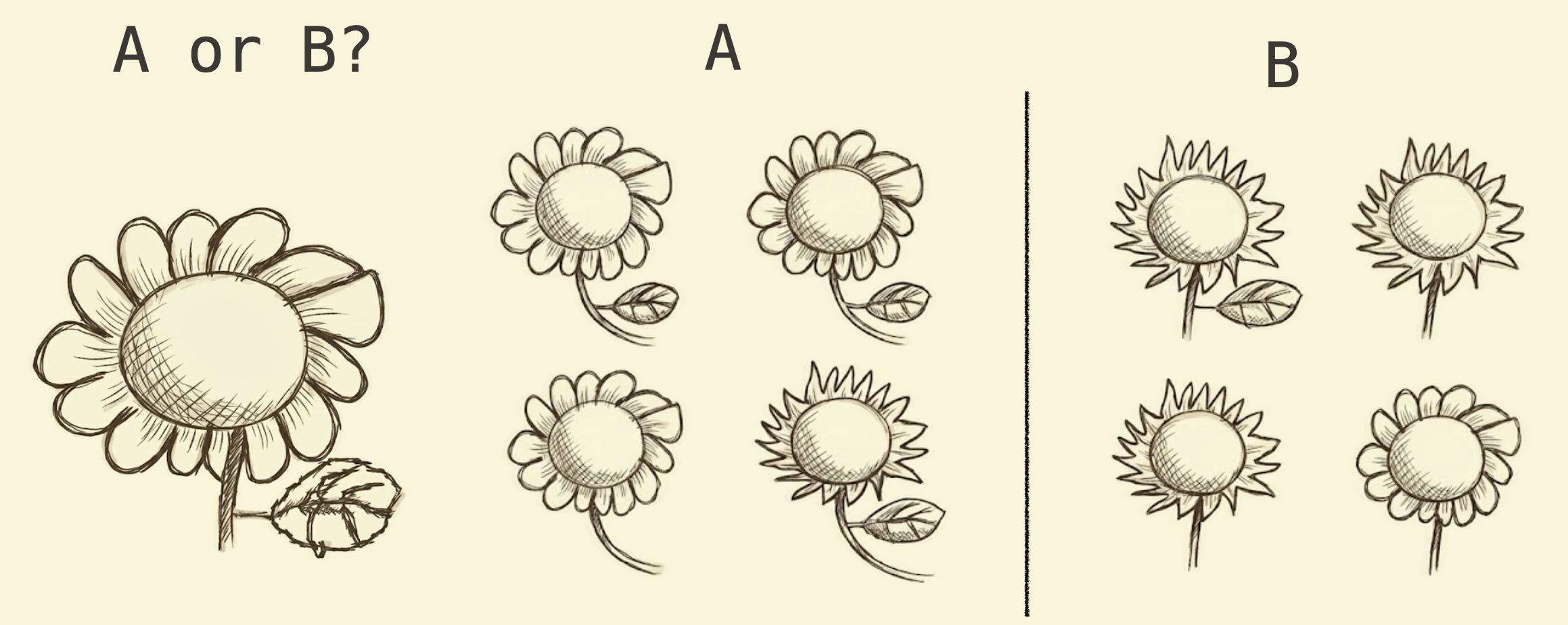

Question 1: Flowers

You see these images. Which grouping feels more natural?

- A: Group by similar appearance (round petals vs. pointed petals)

- B: Group by mixed features (both types together)

Question 2: Animals and Objects

Which pair feels more closely related?

- A: Monkey and banana (contextual association)

- B: Bear and monkey (categorical similarity)

Question 3: The Floating Balloon

Watch this short scene. Why is the balloon moving?

- A: The wind is carrying it (external context)

- B: Air is leaking from the balloon (internal property)

Interpretation:

If you chose mostly A answers, you lean toward metaphorical thinking. You organize the world through categories, similarities, and essential properties. This aligns with what cognitive scientists call “analytic” reasoning, more common in Western philosophical traditions.

If you chose mostly B answers (or A for question 2, B for question 3), you lean toward metonymic thinking. You understand things through context, relationships, and associations. This aligns with “holistic” reasoning, emphasized in East Asian cognitive traditions.

Research by Richard Nisbett and colleagues found that East Asians are more likely to give contextual explanations (the wind, the relationship between monkey and banana), while Westerners focus on intrinsic properties and categorical groupings. These aren’t rigid categories. They’re tendencies shaped by language, culture, and what types of relationships your environment makes salient.

This isn’t just a personality quiz. It reveals something fundamental about representation. If your mind naturally groups by similarity, you’re building a metaphorical semantic space. If you naturally think through context, you’re constructing a metonymic associative network.

Machine learning models do the same thing. Word2vec and modern transformers learn both structures simultaneously, because natural language requires both modes of connection.

From Philosophy to Algorithm

We’ve traced a philosophical thread through linguistics, Buddhist logic, structural anthropology, and cognitive science, and the insight is consistent: meaning is not intrinsic but emerges from patterns of difference, opposition, and relationship. This sounds abstract, but it becomes concrete when you try to teach a machine what words mean. You cannot program in definitions because dictionaries are circular (look up “large” and you find “big”; look up “big” and you find “large”), so instead you need to let the machine discover the structure of language by observing how words relate to each other.

How does word2vec do this? It doesn’t learn what “dog” means by reading a definition but by observing which words appear near “dog” in actual text (“bark”, “pet”, “leash”, “puppy”) and which don’t (“meow”, “aquarium”, “carburetor”). The meaning of “dog” is implicitly defined through this pattern of co-occurrence and exclusion. Word2vec operationalizes Saussure’s insight that meaning is differential, implements Apoha’s theory that concepts are defined by exclusion, builds Jakobson’s feature space where similarity is geometric distance, and captures both metaphoric (similarity-based) and metonymic (context-based) relationships.

What comes next? The next section shows how this works mechanically. How do you turn a philosophical theory about the nature of meaning into working code? How do you represent the continuous space of semantic relationships without imposing arbitrary boundaries? The answer involves vector embeddings, contrastive learning, and a mathematical framework that makes structuralism computable.

Pick a concept you use often (democracy, friendship, justice, art). Try to define it without using synonyms or related terms. You’ll find it’s almost impossible. Now try defining it negatively, through what it is not. Which approach feels more precise? This exercise reveals why structuralism works.